Canton Enamels: Markets and Patronage

During the reign of the Chinese Shunzhi Emperor (1644–61), a ban on maritime trade was implemented on the southeastern coastal areas in order to hold back anti-Qing influences that were coming by sea. In 1683, the 22nd year of the Kangxi Emperor’s reign (1662–1722), the conflict was considered cleared, and the seas officially opened the following year. The Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang, and Shanghai Customs were established to serve as institutions for the management of trade and tariff levies. A Western art form imported to China after the opening of the seas, painted enamel metalwares evidence the exchange and interaction of personnel, techniques, raw materials, and artistic styles among the court, Guangzhou (Canton), and Jingdezhen, with forms, designs, and colours provided by both China and the West. Enamels were regarded as a rarity from the East that enchanted nations, winning acclaim in foreign lands and places.

During the Kangxi and Yongzheng (1722–35) reigns, the main consumers of Canton enamelled metalwares, or Canton enamels, still in their nascent form, were European and local elites. Finished and semifinished products and enamel materials were brought to the Imperial Workshops in the Forbidden City by enamellers upon recommendation by local officials. With the development of Guangzhou’s foreign trade from the Qianlong period (r. 1736–95) onward, Canton enamels were exported to Europe, the British colonies in America, and other parts of Asia and were also ordered to meet the needs of the court. The European and American markets and the Qing court thus became the two main consumers of Canton enamels in the second half of the 18th century, with some products also reaching the Middle East and India by way of merchants from the Islamic region. In the first half of the 19th century, with the advent of the new regimes in Thailand (then Siam) and Vietnam, Canton enamels became popular with the royal families and the upper classes in both regions. At the same time, demand in the Qing court and in Europe and the United States was shrinking, and Canton enamelled porcelain, or guangcai, which was suitable for mass production, flourished. In the late 18th century, the demand for Canton enamels from the Qing court declined sharply, and the withdrawal of the East India Company contributed to the rise of private trade. This led to a more flexible and diverse market; Canton enamels bearing the names of workshops and artisans began to emerge on the market. After the Opium Wars ended in 1860, the market opened further, and signed Canton enamels became more common.

In order to meet the cultural, aesthetic, and functional needs of different consumer groups, Canton enamels show significant differences in shape, pattern, and color palette. The second half of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century, the heyday of Canton enamels, saw greater diversity in design than ever before. From the mid-18th century onward, the decorative style of Canton enamels was recognized by the Qianlong emperor, and the production of enamelled copper for the imperial court gradually shifted from the Imperial Workshops in Beijing to Guangzhou. In addition to purchasing Canton enamels from Guangzhou, the Nguyen Dynasty of Vietnam (1802–1945), with the assistance of Guangzhou artisans, created a royal workshop to produce enamelled copper that closely resembled the Chinese style. By contrast, commissions from the Thai royal family for their use and that of high-ranking monks are more characteristic of their own national style.

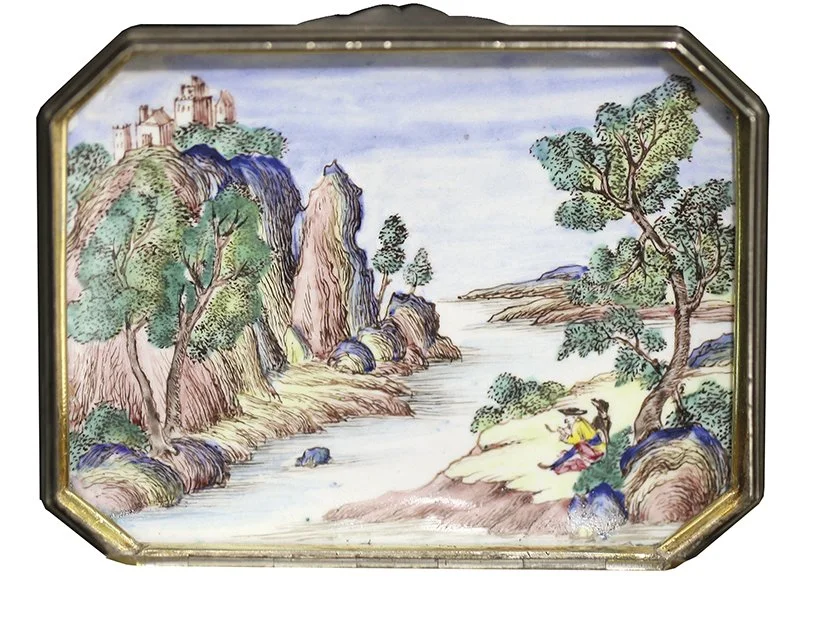

Fig. 1 Snuffbox, inside cover (left) and top of cover (right)

China, Guangzhou (Canton); mid-18th century or earlier

Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong reign (1736–95)

Enamel on silver; 1.8 x 6.5 x 5.3 cm

Chengxuntang Collection

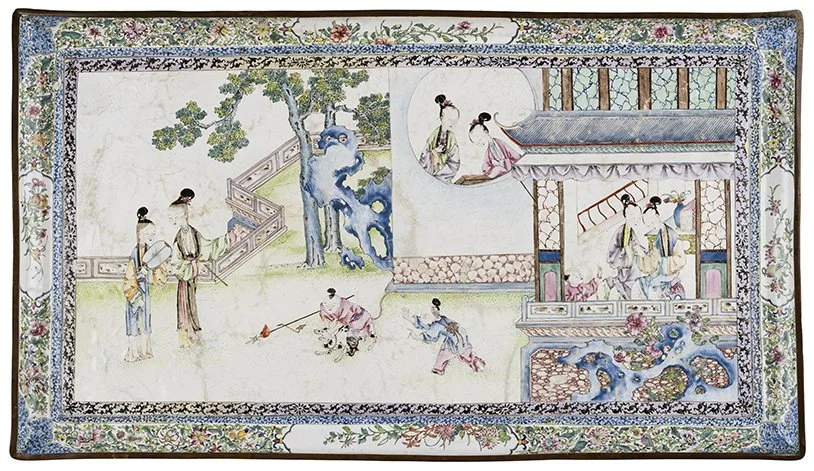

Fig. 2 Lidded jar and detail of base (right)

China, Guangzhou (Canton); c. 1770–80

Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong reign (1736–95)

Enamel on copper; 13.2 x 8.5 cm

Chengxuntang Collection

In this article, we introduce imperial and export Canton enamels in two sections, the first relating to imperial commissions and the second to overseas exports. The export markets of Canton enamels can be further divided into Europe, Islamic regions, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Although Canton enamels had already been brought to the court during the Kangxi and Yongzheng reigns, they did not match the style or quality of the ‘design humbly made by the inner palace’ and were not favoured even in the early Qianlong period. It was not until the 13th year of the Qianlong reign (1748) that the emperor first commissioned Canton artisans to produce enamelled copper vases and jars. That imperial commission was not documented until six years later, in the 20th year of the Qianlong reign (1755), when the Yuanmingyuan Fountain Hall and the Rehe needed a large number of everyday furnishings, tableware, and imperial gifts, and the enamellers at the Imperial Workshops were unable to cope with the demand. (The Fountain Hall is one of the most famous works in Yuanmingyuan, completed in the 16th year of the Qianlong reign [1751], and Rehe was the summer resort of Qing emperors since the Kangxi reign.) Subsequently, there were sporadic imperial commissions of Canton enamels, and they were also sent to the court as annual or festival tributes. Between the 37th (1772) and 50th (1785) years of the Qianlong reign, Canton Customs was repeatedly ordered to reproduce and imitate the enamelled metalware of the Kangxi and Yongzheng periods. At the same time, the Imperial Workshops were more often charged with making cloisonné instead, indicating that the center of production for imperial painted enamel metalware shifted from the Forbidden City to Guangzhou.

Although the Qianlong period was the pinnacle of the production of Canton enamels made for the imperial court, the Qianlong emperor repeatedly issued orders to Canton Customs to limit the types and quantities of enamels and to distinguish between those made for imperial use and those intended as imperial gifts. After the 50th year (1785) of the Qianlong reign, the number of painted enamels produced by both the Imperial Workshops and Canton Customs declined sharply.

The most distinctive types of imperially commissioned Canton enamels are imitations of Western objects, copies of enamelled metalware of the Kangxi and Yongzheng periods, and works produced for the annual and festival tributes.

Fig. 3 Detail of lobed flower-shaped case

China, Guangzhou (Canton); late 18th century

Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong reign (1736–95)

Enamel on copper; 2.5 x 8 cm

Shidetang Collection

Fig. 4 Plate

China, Guangzhou (Canton); mid-18th century

Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong reign (1736–95)

Enamel on copper; 3.7 x 22.5 cm

Private collection

In the 16th century, snuff, which was popular for therapeutic purposes among the Indigenous people of South America, was introduced to Europe and quickly accepted by royalty, the nobility, and the church. By the time of Louis XIV of France (r. 1643–1715), sniffing powdered tobacco became a social norm among the upper classes and was popular across Europe.

From the latter half of the 17th century onward, Western missionaries, envoys, and merchants in China offered snuff, snuff bottles, and snuffboxes as gifts to the Qing court, and they quickly captured the emperor’s attention. At the palace’s Imperial Workshops and in Guangzhou and Jingdezheng, snuff bottles and snuffboxes were made in a variety of materials incorporating the latest painted enameling techniques (Fig. 1). To minimize odor dispersion, larger quantities of snuff were mostly stored in snuff bottles that featured a large body and a small opening, whereas snuffboxes were for smaller amounts and more personal use. Along with incense boxes, snuffboxes became objects of interest, and they were organized and stored among other miscellaneous small decorative objects in the imperial collections. During the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong periods, ready-made Western enamel pieces were often made into small snuff bottles or snuffboxes or added as inlay onto existing pieces. In the 18th century, painted enamel snuffboxes made in Guangzhou and Jingdezhen were sold back to the West.

From the third year to the 52nd year (1738–87) of the Qianlong reign, the Qianlong emperor consciously organized painted enamels from the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and his own reign and stored them in assigned cases at the Qianqing Palace and the Ningshou Palace, establishing two of the most important imperial painted enamel collections. Between the fortieth and fiftieth years of the Qianlong reign (1775–1785), numerous special imperial orders were sent to Canton Customs to make reproductions and imitations of painted enamel metalware of the Kangxi and Yongzheng reigns. Among the earliest reproductions, which have also attracted the most scholarly attention, are objects made after a group of ten works of painted enamel metalware with Kangxi and Yongzheng imperial reign marks. These were originally in the Qianqing Palace, where two reproduction sets arrived in the palace in the forty-second (1777) and forty-ninth (1784) years of the Qianlong reign. An enamelled copper jar in imitation of a bottle with wrapped bundle design was among them (Fig. 2). In addition to these sets, there are other specially reproduced examples, such as a round box with five-colored flowers on a yellow background, a begonia-shaped box, a round box with ball-shaped floral patterns, and a bottle with a loop handle, all of which have the Kangxi imperial mark. In addition to these exact reproductions, there are also copies that varied from the original in pattern, size, and form—in other words, imitations. Because the Qianlong emperor explicitly ordered Canton Customs not to divulge the design of these copies, it is rare to find similar unmarked wares circulating outside the palace.

Fig. 5 Tea tray

China, Guangzhou (Canton); mid-18th century

Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong reign (1736–95)

Enamel on copper; 3.5 x 91.5 x 52.5 cm

Art Museum, Chinese University of Hong Kong (2018.0147)

In the Qing dynasty, it was a routine practice for the palace to place orders during the New Year and other festivals and for local governments to send tributes to the emperor at the same time. Although there is no shortage of innovation in these routine tributes, some models and designs became customary. Among the designs commonly used on such tribute wares, three goats, symbolizing the beginning of the year, are used for the New Year; five types of grains, symbolizing the harvest, for the Shangyuan Festival; the exorcist herb aiye (Artemisia argyi) and a Daoist talisman for the Duanyang Festival (Fig. 3); two celestial beings meeting on the magpie bridge for the Qixi Festival; the characters meaning ‘Eternal Longevity’ for the Emperor’s birthday (Fig. 4); osmanthus for the Mid-Autumn Festival; chrysanthemums for the Double Ninth Festival; a variety of auspicious flowers for the regular flower-viewing events; and so on.

Production of Canton enamels for export began in Guangzhou no later than 1728. The earliest known example is a set of tea- or chocolate-drinking implements, including a basin and a pot with a handle, procured by the British East India Company, which echo the style of the export porcelain that dominated the market. In fact, the small number of early Canton enamels with coats of arms was, like armorial porcelain, associated with tea ware and is the same or similar to it in shape and decoration. Extensive borrowing from export porcelain is evident in the thematic motifs and border decorations of Canton enamels. In addition to responding to the enthusiasm of the imperial family and the powerful and wealthy for painted enamel metalware in China, meeting the demand of overseas markets after the opening of Guangzhou port was one of the main incentives for the production and development of Canton enamels.

The shape and decoration of Canton enamels exported to Europe also show a close relationship with European metal-ware, especially silver, as seen in large round and rectangular trays (Fig. 5), tea boxes, chandeliers, candlestands, wall decorations, teapots (Fig. 6), and more. The European practice of using painted enamels as inlays on clocks, snuffboxes, and furniture also led to the production of large and small geometric pieces of Canton enamels, used not only to satisfy the European market but also as decorative inlays or parts on clocks and watches produced in Guangzhou, as well as on screens and sandalwood pagodas in the Qing palaces. Most Canton enamels sold to Europe and the United States were made in the traditional Chinese decorative language in order to highlight their exoticism, as was also the case with export porcelain, with a few exceptions that were probably made from imported models (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6 Teapot, stand, and warmer

China, Guangzhou (Canton); mid-18th century

Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong reign (1736–95)

Enamel on copper; 34 x 19 cm

Art Museum, Chinese University of Hong Kong (2013.0065)

Fig. 7 Lidded bowl and plate

Vietnam; early 19th century

Nguyen Dynasty (1802–1945), Minh Mạng reign (1820–40)

Enamel on copper; 22.7 x 21.3 cm

Private collection

From the 15th to the 17th century, along with European colonial expansion, Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, England, France, Sweden, and others established their presence in coastal port cities of India to develop trade with Asian countries. After the Qing government lifted the sea ban in 1685, Asian merchants such as Armenians, Muslims, Hindus, Parsis, and others—as well as Jews—were also involved in the Guangzhou trade. They arrived in Guangzhou as early as the end of the 17th century, and they either operated ‘country trade’ as individual merchants or traded with the Hong merchants as agents or ship captains of the East India Company; some even made capital investments through usurious loans to Hong and European merchants. From the 1870s into the 19th century, as the East India Company’s share of trade declined due to bankruptcy, private trade quickly took over, matching or exceeding the former. The number of India-based Asian traders, particularly Parsis, Muslims, and Armenians, increased significantly in Guangzhou. When the trading season ended, they usually returned to India by the same route, but some stayed long-term, renting properties in Macau and Guangzhou, waiting for the next trading season to arrive. The trace of these long-gone merchants can still be glimpsed in fragments of written documents, as well as in a number of surviving Canton enamels that are inscribed with Persian and Arabic inscriptions or that imitate the shape and decoration of Indian and Middle Eastern metal and glass wares (Figs 8–10).

Guangdong and Fujian Customs also had a long history of exchange with Thailand and Vietnam. As both nations entered new dynastic rule with the Chakri Dynasty (1782–present) and the Nguyen Dynasty, respectively, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, their royal families showed great interest in foreign technology and luxury goods. The prosperity of the private country trade, which began in the late 18th century, also facilitated traffic between Guangdong and Fujian and the Chakri and Nguyen dynasties; at the same time, the Chakri and Nguyen royal families were able to obtain Chinese goods directly or indirectly through merchants engaged in the country trade or through ports such as Batavia and Singapore. This exchange was particularly active before and during the 1860s.

From the late 18th to the 19th century, the royal family of the Chakri Dynasty ordered large quantities of porcelain with colourful overglaze decorations, known as bencharong and lai nam thong. They are decorated with mythical creatures of Buddhist and Hindu lore surrounded by verdant tropical vegetation and continuous geometric borders filled with floral motifs (Fig. 11) The surface is covered with decoration filled with local cultural characteristics. Similar shapes and motifs are also found in Canton enamels. A later example is a set of betel nut utensils presented to the United States by the King of Siam in 1876, one of which is marked on the base ‘Yihexiang, 7th year of Tongzhi’.

Fig. 8 Betel set

China, Guangzhou (Canton); late 18th century to 19th century

Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong (1736–95) to Jiaqing (1796–1820) reigns

Enamel on copper; 9 x 28.6 x 23.1 cm

Art Museum, Chinese University of Hong Kong (2019.0022)

Fig. 10 Muskmelon-shaped box

China, Guangzhou (Canton); second half of 18th century

Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong (1736–95) to Jiaqing (1796–1820) reigns

Enamel on copper; 9.7 x 16.3 cm

Shidetang Collection

Fig. 9 Ewer

China, Guangzhou (Canton); second half of 18th century

Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Qianlong reign (1736–95)

Enamel on copper; 31.2 x 23.1 cm

Art Museum, Chinese University of Hong Kong (2016.0015)

Following Kangxi’s system, Emperor Minh Mạng (r. 1820–40) of the Nguyen Dynasty set up imperial workshops in the Thái Hòa Palace to make enamel, glass, porcelain, and other royal wares, including enamelled copperware items that range from architectural ornaments and everyday objects to ceremonial objects, whose shapes and decorations show strong Chinese elements. Some of the painted enamels are even signed with imperial reign marks (Figs 12–13). Incorporating enameled metal pieces as inlays on palaces and imperial tombs was characteristic of the Nguyen Dynasty. Both the National Museum of Thailand and the Hue Royal Antiquities Museum have collections of Canton enamels of varying quantities and no specific regional characteristics, which are probably general trade goods from Guangzhou. These enamelled copper pieces from Thailand and Vietnam are typical of 19th-century Canton enamels.

In addition to the imperial and export markets, there were also Canton enamels made for the domestic market and general merchandise, with no specific destination market. The former includes a number of fine pre- and post-Yongzheng pieces that were intended for use by the upper classes. The latter is characterized by a group of late 18th-century and especially 19th-century wares with workshop or trade marks, of varying fineness, more like general specialty crafts for foreign travelers to China. After the First Opium War in 1840, the end of the Canton System and the opening of the five treaty ports gave foreigners more access to trade. Especially after the Second Opium War in 1860, the movement of foreigners within China became freer. Hong Kong, Macau, Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Beijing were the places where foreigners were most concentrated and where trading houses flourished the most.

Xu Xiaodong is Associate Director of the Art Museum at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Fig. 11 Jar

Thailand; first half of 19th century

Rattanakosin Kingdom (1782–1939)

Basse-taille enamel on silver with gold knob; 8.6 x 6.5 cm

Private collection

Fig. 12 Mug

Vietnam; c. 1820–40

Nguyen Dynasty (1802–1945), Minh Mạng reign (1820–40)

Enamel on copper; 11.3 x 10.8 cm

Private collection

Fig. 13 Lidded bowl

Vietnam; first half of 19th century

Nguyen Dynasty (1802–1945), Minh Mang (1820–40) to Tự Đức (1847–83) reigns

Enamel on copper; 9.5 x 11.9 cm

Private collection

Selected Bibliography

The First Historical Archives of China and Art Museum, Chinese University of Hong Kong, eds, Archives of the Palace Workshops of the Qing Imperial Household Department, Beijing, 2005 (in Chinese).

Luisa E. Mengoni, ‘Adapting to Foreign Demands: Chinese Enameled Copperwares for the Thai Market’, in Anne Håbu and Dawn F. Rooney, eds, Royal Porcelain from Siam: Unpacking the Ring Collection, Oslo, 2013, pp. 107–24.

Shih Ching-Fei and Wang Chongqi, ‘Imperial “Guang Falang” of the Qianlong Period Manufactured by the Guangdong Maritime Customs’, Taida Journal of Art History, no. 35 (2013): 134–51 (in Chinese).

Xu Xiaodong, ‘The Production and Sale of Painted Enamel on Metal in Guangdong during the Qing Dynasty, with Comments on Canton Enamel and Its Dating’, Zhejiang University Journal of Art and Archaeology, no. 5 (2022): 99–190 (in Chinese).

This article featured in our Sep/Oct 2022 print issue.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.