Tao Yuanming Returning to Seclusion: The Tale of Charles Lang Freer’s ‘Most Interesting and Beautiful Scroll’

If narrative paintings could talk, Tao Yuanming Returning to Seclusion (Fig. 1, section 1) would have multiple stories to tell—starting with how it came to be part of the first major American collection of early Chinese paintings, assembled by the Detroit industrialist Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919), who donated his collection to the Smithsonian Institution and founded the Freer Gallery of Art. In the final decade of his life, Freer made early Chinese painting (pre-14th century) one of his collecting priorities. He discovered Tao Yuanming Returning to Seclusion, an early 12th century handscroll attributed to the Northern Song literati painter Li Gonglin (c. 1040–1106), among a group of 34 Chinese paintings sent to him by the Shanghai dealer K. T. Wong in the summer of 1919. Wong had been an important source of Chinese paintings, jades, and other antiquities since 1916, shipping objects in batches to Freer’s mansion in Detroit. Wong knew precisely what paintings Freer was after: in a letter to Wong in February 1915, he had added a handwritten postscript in heavy black ink to remind him, ‘Do not send me any Ming or later pictures, I buy only Song and earlier paintings. CLF.’

Correspondence, invoices and checklists exchanged between the Detroit collector and the Shanghai dealer also tell the story of Freer’s acquisition process and his determination to keep building a significant collection of early Chinese paintings in the final months of his life. In May 1919, Wong shipped 34 paintings in two cases to Freer’s Detroit address. When the paintings arrived in June, Freer was residing at the Gotham Hotel in New York, where he could be near to his doctors and close friends. Now seriously ill, it wasn’t until early August that Freer responded to Wong—after the paintings were brought to New York and he had gained enough strength to examine the shipment with his trusted assistant, Katharine Rhoades (1885–1965). In a letter dated 6 August, Freer explained to Wong:

I am now able to write you fully in regard to your recent shipment to me of thirty-four Chinese paintings, as I have examined with great care and much interest, every specimen of the entire lot, and I am now writing to you to tell you that I shall be glad to purchase twenty-four (24) paintings out of the thirty-four (34) sent to me for examination. Of these 24 paintings, 20 of them will go into my collection and 4 of them I have presented as gifts, 2 to Mrs. Eugene Meyer Jr. (Agnes E. Meyer, 1887–1970), and 2 to Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer (Louisine W. Havemeyer, 1855–1929).

Your total of the prices for these 24 paintings comes to $36,800.00—and from that amount I have made the usual deduction of 50%, which brings the total price which I owe for these 24 paintings, to $18,400.00, but inasmuch as I feel that several of these paintings are most interesting and beautiful, I should like to have you accept from me an additional $1,600.00, for them, which will bring the total payment to $20,000.00.

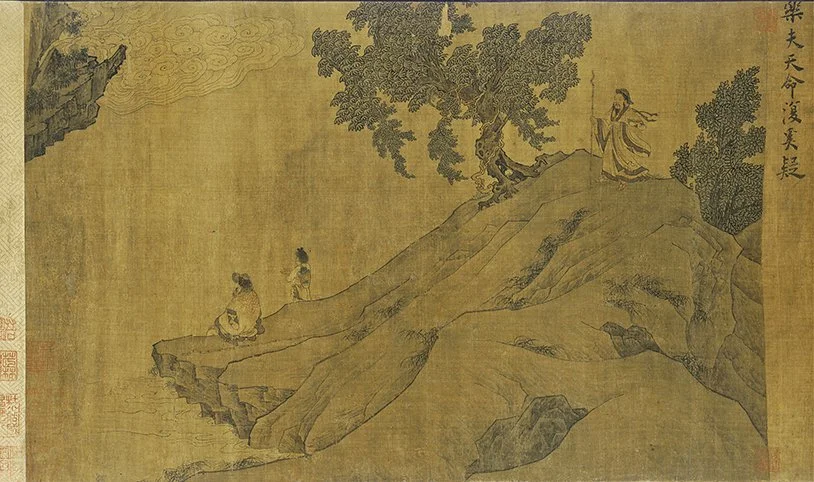

(Figs 1,2 and 3) Details of Tao Yuanming Returning to Seclusion

China, Northern Song dynasty, early 12th century

Traditionally attributed to Li Gonglin (c. 1049–1106)

Handscroll, ink and colour on silk

Width 37 cm, length 518.5 cm

Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, DC

Gift of Charles Lang Freer (F1919.119)

Freer’s offer of $20,000 for 24 paintings was accepted by Wong in a telegram on 22 September, just three days before Freer died.

Among the paintings were two handscrolls attributed to one of Freer’s favourite artists, Li Gonglin. Wong’s checklist described the two handscrolls as two parts of one scroll that illustrated a famous prose poem, Returning Home, written by the 4th century scholar-recluse Tao Qian (365–427). The two scrolls were remounted together in 1929 under one accession number and the title Tao Yuanming Returning to Seclusion. The story of Tao Qian—or Tao Yuanming—was widely known among Chinese intellectuals in subsequent centuries. Tao served as a local magistrate in Jiangxi province for only eighty days, at which point he decided to quit his post. What seemed an impulsive action is explained in Tao’s preface to his poem: within a few days of taking the position, Tao said, he knew that he had made a mistake. The work went against his very nature, so he returned home. Tao’s decision resonated with later Chinese intellectuals who were educated through the Confucian examination system and who were expected to enter an elite corps of scholar-officials assigned to administer local government affairs. Tao Yuanming rejected this model—choosing home life over official duty (Fig. 2).

(Fig. 2) Section 2 of Tao Yuanming Returning to Seclusion, showing the scholar-recluse at home

Whether Charles Lang Freer himself identified with the Tao Yuanming story remains unclear. It is more likely that Freer responded to the aesthetic qualities in the handscroll: the fine-line brushwork and antiquarian figure style associated with Li Gonglin; the subdued colour palette and aged silk; the abundant patterns and textures in foliage and rocks; the series of pictorially rich compositions alternating between landscape and residential scenes; and the bearded gentleman in a long robe, leopard skin shawl and gauze hat, leading the viewer forward through the narrative (Fig. 3). One also suspects Freer enjoyed the diagonal composition underpinning each scene—something he admired in Japanese prints and works by his friend James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903). According to Agnes Meyer (1887–1970) in her pioneering 1923 monograph about Li Gonglin, ‘[Tao Yuanming Returning to Seclusion] brought Mr. Freer great happiness to discover shortly before his death.’

After a decade of ‘scientifically and determinedly’ searching for early Chinese paintings, Charles Lang Freer rightly singled out Tao Yuanming Returning to Seclusion among the group of paintings shipped from Shanghai by K. T. Wong. The handscroll was the last masterpiece of early Chinese painting handpicked by Freer for his gallery—a tribute to a Detroit industrialist with an unusually sharp eye. Ingrid Larsen was a research specialist for the project to catalogue Song and Yuan paintings in the Freer Gallery of Art (1997–2007). She is currently an independent scholar of Chinese art history and a teacher of Chinese at The Potomac School in McLean, Virginia.

(Fig. 3) Section 7 of Tao Yuanming Returning to Seclusion, showing, on the top of the hill, a bearded gentleman in a long robe, leopard skin shawl and gauze hat

Ingrid Larsen was a research specialist for the project to catalogue Song and Yuan paintings in the Freer Gallery of Art (1997–2007). She is currently an independent scholar of Chinese art history and a teacher of Chinese at The Potomac School in McLean, Virginia.

Selected bibliography

Ingrid Larsen, ‘Don’t Send Ming or Later Pictures—Charles Freer and the First Major Collection of Chinese Painting in an American Museum’, Ars Orientalis 40 (2011): 6–38.

Thomas Lawton, Chinese Figure Painting, Washington DC, 1973.

Agnes Meyer, Chinese Painting as Reflected in the Thought and Art of Li Lung-mien, New York, 1923.

Song and Yuan Dynasty Painting and Calligraphy Web Resource, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 2010 <http://www.asia.si.edu/ SongYuan/default.asp>.

This article featured in our Nov/Dec 2014 print issue.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.