Historical Mapping of Guangdong and Guangzhou

Historical maps of Guangdong, a seaboard province in southern China, belong within several map lineages associated with Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) cartographic projects that include new surveys as well as those related to maritime trade and coastal defence of the region. The numerous large and small ports along its coast have long participated as terminal and transit points in many maritime trade routes; meanwhile, its largest coastal city, Guangzhou (Canton), has long been an important trading and diplomatic port. Examining maps in the MacLean Collection that primarily span the 19th century provides a glimpse into the extensive and rich history of the province and its principal city.

The records of that history begin in the Tang dynasty (618–907). Court historians have long included the region in large-scale chronicles, beginning with a text in the geography section (dili) of the New History of the Tang Dynasty (Xintangshu), written by the prime minister and renowned geographer, Jia Dan (729–805). His text titled ‘The Route to the Foreign Countries across the Sea from Guangzhou’ (‘Guangzhou tong haiyi dao’), from about 800, is the earliest extant document, from either China or the Arabic world, that describes the maritime route between Guangzhou and the Persian Gulf. This important early Arabic connection continued throughout the centuries with a local Muslim community located in Guangzhou, as confirmed by the presence of a mosque first built in the 7th century, seen on the late Qing maps in the MacLean Collection. The region has been locally active in trade routes—of southeastern and eastern Asia; from Persia, Arabia, and India; as well as later from Europe—that all came through the Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea to Guangzhou.

1

Guangdong Province

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), c. 1800

Hanging scroll: ink and colours on paper; 294.6 x 172.7 cm

MacLean Collection

During the Song dynasty (960–1279), the central government restricted access to China, and maritime embassies from other countries that travelled to China as part of the so-called tribute system were limited in their access to China only through the port of Guangzhou. A number of those countries included Siam (today’s Thailand) and Annam (today’s Vietnam), and later several European nations also entered China only via Guangzhou.

In the late Ming dynasty, as a direct result of rampant maritime piracy, a new map type known as ‘coastal defence maps’ (haifang tu) were produced. The first significant work of this kind was the Illustrated Compendium on Coastal Strategy (Chouhai tubian) printed in 1562 by Zheng Ruozeng (1503–70). This established the style of maps on maritime defence, presenting a series of coastal maps, beginning in the south with maps of the Guangdong coast and ending in the north with maps of the Liaoyang coast.

2

Detail view of figure 1, showing Nan-ao island

3

Detail view of figure 1, showing Guangzhou

During the Qing dynasty, new local gazetteers were produced as part of several administrative changes that occurred. Of note were the Guangdong yutu of 1685, compiled by Jiang Yi (1631–87) and Han Zuodong (act. 1685) with 99 maps of the province, and the Guangdong tongzhi, printed in Guangzhou in 1731 and complied by Hao Yulin (act. 18th century) and Lu Zongyu (act. 18th century). And finally, there were the massive Jesuit surveys completed in 1714, becoming the Imperially Commissioned Overview of Imperial Territories (Qinding huangyu quanlan, nicknamed ‘Kangxi atlas’), a route book that constituted the ultimate guide to Qing road and waterway networks. All of these mapping projects inspired new maps of the Guangdong region.

One example is a beautifully rendered oversized manuscript map, with a title found in the top right of the text block below the map, which simply reads ‘Guangdong Province’ (Guangdong sheng) (fig. 1).

4

Map of Guangdong province

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), c. 1739

Sheet map: ink and colours on paper; 100 x 163 cm

Photo © 2022 Christie's Images Limite

The overall composition visually emphasizes Guangdong’s maritime qualities: half of the visual space represents water, showing the provincial coastline and Pearl river delta with related river systems that tie into the Pearl river as all coloured in green, in contrast to European maps of the period that preferred blue for representing water. The map is rendered using painterly techniques, as seen in a detail of Nan-ao island off the coast (fig. 2).

The variety of brushstroke types for texturing the outcroppings of rock and leaves of the trees as well as the skilled application of colours, blue and green in particular, confirm the hand of a highly skilled painter. Nan-ao as an important island off the Guangdong coast had a long and varied history. Its identity transformed from smuggler-and-raider stronghold to official garrison town in the Ming dynasty, and it continued as an important participant in the off-shore coastal defence system of the Qing dynasty. Here the walled fortification, named Nan-ao garrison (zhen), is one of many fortifications and garrisons included in the map, confirming its presentation of coastal defences. Throughout the stylized wave patterns of ocean water are rendered a dozen different types of open-water, coastal, and river vessels, showing the diversity of ship types of the period. The text blocks along the bottom of the map provide information related to the borders of the province, as well as data about its prefectures, counties, and cities. Important ports like Guangzhou, Macao, and Hong Kong are shown (fig. 3).

Guangzhou is rendered simply as a walled city divided into the ‘old’ and ‘new’ sections with a number of well-known but here unnamed buildings, with two small fortifications placed close to shore. Maritime distances between Guangdong coastal counties like Xuwen, Haiansuo, and Haikou with important neighbouring ports on Hainan island (across the Qiongzhou strait in northern Hainan) are provided in the lines of text around the city, along with other ports like Dongjing (today’s Hanoi, in northern Vietnam) and Annam (Xijing, in central Vietnam) reminding the viewer of the city’s important trade-route relationships.

5

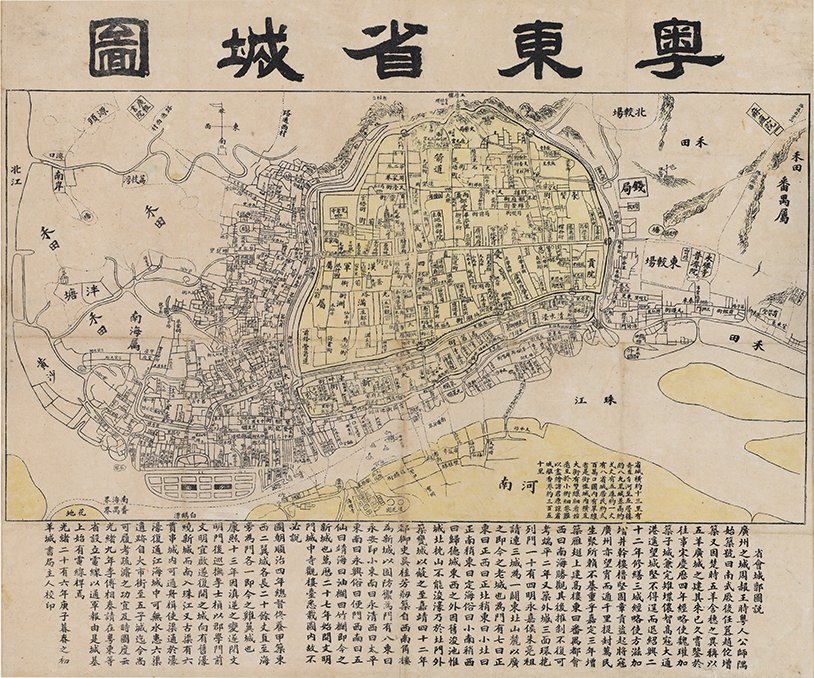

Map of the Capital City of Guangdong (Guangdong shengcheng tu)

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

Album: ink and colours on paper; 51 x 35 cm

MacLean Collection

The MacLean manuscript map of Guangdong province belongs within several map lineages associated with Qing cartographic projects. Its composition and most of the textual information are derived from a woodblock printed map entitled Guangdong Entire Province Explanatory Map (Guangdong quansheng tushuo) printed about 1739 (fig. 4); the MacLean map is twice as large and was created about 1800.

There are three known copies of the printed map, located in the Bibliotheque Nationale de France, the Royal Geographic Society, and a private collection (formerly Robinson and Getty collections). The printed version states that 88 maps were consulted, including coastal defence maps, trade route maps, various local gazetteers, and the Jesuit surveys completed in 1714, as part of the Kangxi atlas project.

The MacLean Collection also has a number of maps of the port city of Guangzhou, including a fairly simple but elegant folded-album-sheet manuscript map painted on gold-flecked paper and mounted with a thick brocaded cover, titled Map of the Capital City of Guangdong (Guangdong shengcheng tu), that is, Guangzhou (fig. 5).

6

Detail view of figure 5, showing mosque and west gate

7

Detail view of figure 5, showing Five Story Tower

The title slip on the cover provides the same title as well as another slip that reads, ‘Treasured collection of Li Gong’, referring to an as-yet-unidentified collector. In the upper left of the map, there is a brief historical description of naming in the area followed by a square red seal reading ‘meritorious scholar Chen’, the as-yet-unidentified but likely creator of the map. Below that, the map key designates five different colours, using gold and mineral pigments: green for water (as seen on the previous maps), red for noteworthy places, gold for roadways, blue for mountains, and grey for city walls. The materials used for producing and mounting this map (gold-flecked paper, gold and mineral pigments, and heavy brocaded silk) indicate it was probably imperially sponsored and gifted to Mr Li Gong.

All of the toponyms and noteworthy places are surrounded by double-red-lined rectangular boxes. One noteworthy place and the only building shown that is not in the style of a Chinese hip-and-gable architectural structure is the mosque with its domed tower, still located in the old city near the western gate, named here ‘Muslim tower’ (huihuita) (fig. 6).

The mosque, first built in the Tang dynasty, making it the oldest extant mosque in China, is named the Huaisheng Temple and nicknamed the ‘shining pagoda’ or ‘lighthouse’ (guangta), as it was until the early 20th century the tallest building in Guangzhou and served as a nighttime beacon across the city. Another distinctive and still-present building, built in 1380 at the beginning of the Ming dynasty as part of the defence wall in the northern hills of the city, is the Zhenhai Tower, later known as and labelled here as the Five Story Tower, found at the northern edge of the city wall (fig. 7). Both of these structures can be found on the earlier provincial map as well as European maps of Guangzhou from the late 17th century (fig. 8).

8

Plan of Guangzhou (Kanton, in Platte Grondt)

By Pieter van der Aa (1659–1733); c. 1670

Ink and colours on paper; 36 x 30.5 cm

MacLean Collection

The Plan of Guangzhou was produced about 1670 by Pieter van der Aa (1659–1733), a prolific Dutch publisher of maps and atlases. The map is based on the earlier work of Johan Nieuhof (1618–72), a traveller and explorer with the Dutch East India Company, and his written account of his roundtrip journey from Batavia to Guangzhou and finally Beijing, from 1655 to 1657, titled An Embassy from the East-India Company of the United Provinces, to the Great Tartar Cham, Emperor of China. Access inside the walled city was forbidden to all foreigners, explaining why so little information other than a simple grid is provided for that space.

This map presents an interesting combination of at least two different perspectives: the plan, or cadastral, view of the ‘old’ city proper, with its distinctive keyhole shape, is imbedded in the elevated view of the surrounding harbour and mountains. Floating in the sky, supported by cherubs, are texts in Dutch: the title on a ribbon in the upper left and a list of fifteen notable places on a banner in the upper right. In the foreground, the two fortifications, also noted on the previous provincial map and known as ‘folly forts’ (the European name for military forts built in shallow water), are clearly depicted while farther back the city wall is presented in profile. These forts were originally part of the Chinese coastal defence system and later became Dutch and French forts. The mosque is drawn as a minareted tower without a label, near the building labelled ‘I’, the Palace for the Young King (NL.: Pallays van der Jongen Koning).

9

Map of Guangzhou in Guangdong Province (Yuedong sheng chengtu)

China; Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 1900

Sheet map: ink and colours on paper; 51 x 62 cm

MacLean Collection

The Guangdong region has several specifically historical toponyms, like the ancient name associated with the region of China generally south of the Yangzi river, known as Yue. During the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE–8 CE), the Pearl river delta area became known as the Southern Yue (Nanyue) region. The unique toponym for Guangdong’s Yue and its associated Chinese character is still in use today (for example, on license plates). This map title uses that unique character and translates literally as ‘map of the provincial capital in eastern Yue’ (Yuedong sheng chengtu), or Map of Guangzhou in Guangdong Province (fig. 9).

The map is dated to the 26th year of the Guangxu reign (1875–1908) of the Qing dynasty, or 1900. A section of the Pearl river meanders along the bottom of the map. Above that the section in yellow is the keyhole-shaped walled part of the ‘old’ city. The large body of text below provides a lengthy paragraph on the history of the naming of this provincial capital city and the region. The other smaller block of text provides information about the physical characteristics of the city. Historically, maps in China were produced by the central or regional governments. This map is unusual in that it was published in Chinese by a local commercial enterprise, the Yangcheng bookstore. The bookstore uses one of the historical nicknames for Guangzhou, ‘the city of rams’ (yangcheng); another nickname is ‘the city of five rams’ (wuyangcheng), from the story of the five immortals who rode into the city on five rams, which were later turned to stone.

During the second half of the 19th century, several bilingual maps of Canton (Guangzhou) were produced by European and American publishers. A bilingual map in the MacLean Collection is the Map of the City and Entire Suburbs of Canton, printed in 1860 (fig. 10).

10

Map of the City and Entire Suburbs of Canton

By Daniel Vrooman (1818–95); 1860

Sheet map: ink and colou rs on paper; 126 x 74 cm

MacLean Collection

It was compiled by Daniel Vrooman (1818–95), an American missionary sent by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to serve in China from 1852 to 1866. He continued to work as an independent missionary in the area, after which he became superintendent of a mission to the Chinese based in Victoria, Australia, from 1878, and he retired in 1891 to California.

Although the old walled city was still closed to all foreigners, Vrooman hired local informants and a convert he trained in scientific measurement methods to assist him. He made his first manuscript maps in 1855, the first bilingual maps of Guangzhou with naming in Chinese and English. The 1860 map was printed as a bilingual large-scale plan. The walls of the inner and outer walled city are outlined in red, with the city gates all labelled. Details include named streets, notable buildings, officials’ residences, parade grounds, temples, forts, gardens, ponds, and the many rice paddies surrounding the city. There are trade-related buildings along the waterfront, including pack houses, store houses, coal depots, and lumber yards.

Beginning from 1757, the Chinese government employed what became known as the Canton system, which made Guangzhou the sole port of entry for European and American goods into China. A cohort of Chinese merchants, the cohong, mediated between the Chinese government and foreign traders, and they operated out of the Thirteen Factories area noted on this map. The factories were destroyed by fire in 1822 and rebuilt. The location of the Old Factories section, where the American and English factories had recently been located but were destroyed during the Second Opium War (1856–60), on the waterfront, are also labelled. The island of Shamian, outlined in yellow in the lower left corner, was created in 1859 to house foreign traders. The 1860 state of this map depicts these changes and shows the land reclamation that made possible the creation of Shamian.

11

Map of Canton, in The Tourist’s Guide to Canton, the West River, and Macao

By R. C. Hurley, Hong Kong; 1895

Folding pocket map: ink and colour on paper; 37 x 47 cm

MacLean Collection

Finally, a small foldout map, which primarily includes the important landmarks already mentioned, is found in The Tourist’s Guide to Canton, the West River, and Macao (fig. 11).

This pocket-size guide was printed in Hong Kong by R. C. Hurley and published by Noronha and Company in 1895 and includes 87 pages of text, images, a dictionary, shopping advice, and maps, along with forty pages of advertisements, affirming the popularity of English-speaking tourists travelling to Canton at the end of the 19th century.

This brief survey of primarily late Qing Chinese maps showing Guangdong and Guangzhou provides just a glimpse into the range of materials, production qualities, and scales—from low- to high-end, from manuscript to print, from oversize wall map to fold-out pocket map—and the use of multiperspectival views, confirming the breadth of sponsors and intended viewers for maps of all kinds.

Richard A. Pegg is Director and Curator of Asian Art for the MacLean Collection Asian Art Museum and Map Library. The author thanks Yifawn Lee for her support and promotion over the past decade in publishing a continuing series of articles related to the historical mapping of East Asia.

Selected bibliography

Jonathan Andrew Farris, Enclave to Urbanity: Canton, Foreigners, and Architecture from the Late Eighteenth to the Early Twentieth Centuries, Hong Kong, 2016.

Valery M. Garrett, Heaven is High and the Emperor Far Away: Merchants and Mandarins in Old Canton, Oxford, 2002.

Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt, ‘China’s Earliest Mosques’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 67, no. 3 (September 2008): 330–61.

Paul A. Van Dyke and Maria Kar-wing Mok, Images of the Canton Factories 1760–1822: Reading History in Art, Hong Kong, 2015.