‘To praise it, one need only say it was from China’: Chinese Textiles in Portugal in the Early Modern Period

A significant number of Chinese textiles, dating mainly from the 17th and 18th centuries, can be found in Portuguese collections—both public and private—often existing in their original contexts of use. They are the result of the production and trade of Chinese textiles for the Portuguese market during the early modern period—and the enduring popularity those textiles experienced from the moment of their introduction. This is the conclusion of the study that we have dedicated to Chinese textiles in Portugal, with a view to identifying pieces, their particularities, and the historical-artistic context that underlies their adoption and use in Portugal (Ferreira, 2007 and 2011).

Before the age of Portuguese territorial expansion into Asia, the importation of Asian textiles to the port of Lisbon would have been sparse and dependent on existing routes, mainly those associated with the Silk Routes. Even so, some earlier fragments are known, evidence of the allure these objects held for elites and the ecclesiastical milieu, in Portugal and all over Europe at the time. Gonçalo Pereira (c. 1280–1348), archbishop of Braga between 1326 and 1348, was laid to rest in his funeral monument covered in the finest fabrics produced at the time in both the European and extra-European context. A number of the garments bear features that suggest Central Asian and Chinese origin (Monteiro, Claro, Dias, and Candeias, 2014, 89–90).

Everything changed in the 16th century. After the Portuguese arrived in Calicut (on the southwest coast of India) in 1498, they established a pioneer commercial circuit of Euro-Asian trade via the Cape Route, which ensured direct maritime trade between Portugal and India and the regular arrival of Asian commodities and products for distribution to eager consumers across Europe. Gaspar Correia, the chronicler who narrated their epic journey, recounted that, on the return trip to the kingdom in 1501, captain Pedro Álvares Cabral and his men loaded spices, porcelains, and golden coffers full of damasks and satins from China—all never before seen in Portugal (Correia, 1858, 226).

Fig. 1 Cope

China; c. 1630

Silk satin; silk thread; gold-wrapped paper thread; double twisted silk thread; paper rolls; 138 x 286 cm

Museu da Irmandade de Santa Cruz, Braga

Photo © Maria João Ferreira

Subsequently, and especially after the conquest of Malacca in 1511, the Portuguese not only met and traded avidly with Chinese merchants but also strove to increase their knowledge about the region in order to grow and support this lucrative trade relationship. To that end, they launched two official expeditions to China: in the summer of 1513, during which they reached the island of Taman, near Canton, and in 1515. The success of both, considering the profits from the sale of the products acquired there— several times greater than the amounts invested— encouraged King Manuel I (r. 1495–1521) to organize an embassy to Beijing, headed by the apothecary Tomé Pires (1465–1540). The mission fared badly for the Portuguese, who were barred from entering the country; despite this, they maintained commercial contacts through smuggling in the coastal provinces of southern China. Finally, in 1557, Ming officials allowed a permanent Portuguese settlement in Macao, in the Pearl River Delta in the Guangdong Province. A 1554 treaty with the local authorities allowed the Portuguese to trade in exchange for the payment of taxes. As a result, the Portuguese were able to access and participate in the important biannual fairs of Canton.

Chinese textiles, with their vibrant colors, sophisticated techniques, and fine materials, became very appreciated in Portugal and were gradually imported and incorporated into daily sacred and secular life, both in the kingdom and in the colonial empire. These items, once shrouded in an aura of curiosity and fascination and reserved only for the strata of society with the most economic and social power, became the object of more regular and organized trade and, consequently, also became more accessible. Beyond luxury goods, the manufacture and marketing of products of varying quality contributed greatly to the popularization of Asian textiles, as did the fact that some were designed specifically for Portuguese tastes and needs.

Chinese-produced ornaments for Catholic worship that are still extant in Portugal, such as liturgical vestments and decorations for sacred spaces and processions, are good examples. Most of this type of export textile was intended for various missionary contexts in Asia, under Portuguese (and Spanish) patronage, which required certain ornaments that were necessary for the celebration of the liturgy. But many pieces were channelled to Portugal, mainly through private trade and efficient ecclesiastical networks, which were responsible for their generalized distribution throughout the country by means of orders and gifts. For example, a set in the possession of the Irmandade de Santa Cruz (Holy Cross Brotherhood) in the city of Braga (Fig. 1) was sent at its request, in the 1630s, by an influential and powerful merchant from Macao, a native of the council of Braga, who was responsible for supplying other pieces to various institutions in the region. Another vestment, from the church of Santo Aleixo da Restauração, in the town of Moura, was part of a royal gift from King Pedro II (r. 1683–1706) to the Convent of Tomina, in Alentejo (Fig. 2). In each case, it has been possible to establish a connection to written documents that allow the pieces to be dated and shed light on the means used to obtain them, thus helping to identify characteristics of production in this period.

Fig. 2 Dalmatic

China; c. 1650

Silk satin; silk thread; gold-wrapped paper thread; double twisted silk thread; cotton/hemp (?) cord; 110 x 96.5 cm

Igreja de Santo Aleixo da Restauração, Moura

Cross-analysis of contemporaneous documentary sources, such as inventories and record books, the surviving objects themselves, and the accounts of sacro-profane events, corroborates how enthusiastically these ornaments were received by the urban and rural communities that attended events. Research also confirms the objects’ effective integration within local liturgical practices, particularly during celebratory events in which they were, in part, displayed as signs of prestige and power.

Such visually distinct and appealing objects embodied their owners’ involvement in the Portuguese venture in Asia, especially in its catechetical and evangelizing dimensions. Period chroniclers focused on these objects, not only highlighting their presence (in contrast to Indian textiles, which were often ignored) but also greatly admiring them: praising the nobility of the materials used, their originality, the liveliness and naturalism of the decorative programs they displayed, and their distant origins. Siro Ulperni, who recorded the canonization feast of Saint Magdalene of Pazzi in 1669, invokes precisely this argument when describing the set of satins, with various colours, furnishing the church of the Carmelite convent in Lisbon: ‘To praise it, one need only say it was from China’ (para justamente gagabala, basta dizer que era da China) (Ulperni, 1672, 15).

The manufacture of these articles in China required specific instructions connected to their intended liturgical use; the Catholic Church prescribed the colours of the liturgical calendar (white, green, red, purple, and black), the morphology, and even the dimensions for different types of implements. Some guidelines regarding design would have been provided by Portuguese merchants and priests in the form of engravings, drawings, brief (oral or written) instructions, or pieces with similar parameters. These would serve as models from which the Chinese artisans could either copy or conceive variations around an element or composition.

Fig. 3 Altar Frontal

China; 2nd half of 17th century

Satin embroidered with silk and gold-wrapped paper thread; 100 × 192 cm

Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência da Universidade de Lisboa (Inv. ULisboa – MUHNAC-11)

Photo © José Vicente

Fig. 4 Cope

China; 2nd half of 17th century

Satin embroidered with silk and gold-wrapped paper thread; 132 x 283 cm

Museu Militar do Bussaco, Bussaco

Photo © José Vicente | Agência Calipo 2022

A combination of Chinese motifs, Christian elements, and local European iconography characterize these export textiles, which were made primarily with techniques and materials associated with Chinese textile production, including silk, gold-wrapped paper thread, and double-twisted silk cord. For example, an altar frontal with a central panel is dominated by a two-headed eagle and bordered by panels of peony vases; these are flanked by qilins and lions playing with a brocade ball, two important mythical beasts in Chinese mythology. Its decorative program is completed by a central medallion on the frontlet, bearing the IHS Christogram and three nails on the bottom, traditionally associated with the Jesuits, or Society of Jesus (Fig. 3). In this piece, the European theme stands out, partly due to its prominent place in the Catholic liturgy. A very similar piece can be found in a different set, whose cope is nevertheless entirely filled with Chinese floral and animal motifs, mostly embroidered with gold-wrapped paper thread (Fig. 4).

Besides being visually effective, flowering branches of peonies radiating from rocky mounds—in conjunction with other species, such as lotus flowers and chrysanthemums—can be adapted easily to any kind of area. They are the base of most of the compositions, often combined with various species of birds and mammals, which are nearly always represented in pairs, as well as butterflies and insects, perched or flying among the plants. These elements, through their level of detail, rich colour schemes, and designs devised to recreate the image of Paradise, still captivate and charm Portuguese viewers whenever they come across them in religious celebrations, inside and outside churches.

A set of vestments from the now-extinct Convento do Deasagravo, in Lisbon, currently held in the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (Inv. 1208-1216), features different subjects. The set comprises two dalmatics, a chasuble, two stoles, three maniples, and a cope, all decorated with flowers, musical instruments, bats, and the eight auspicious symbols of Buddhism. Such a motif might be surprising in a Catholic context. However, in practice, what mattered more than the theological content—about which the majority of the population was unaware— was the artefacts’ beauty and the fact that they came from the mythical China, which had been part of the Western imagination since ancient times. Moreover, in the same manner that the Church of Rome often repurposed fabrics that were originally produced for secular ends, such as furnishings or apparel, it also integrated non-European textiles into the creation of liturgical vestments.

Fig. 5 Chasuble

China; 1st half of 17th century

Silk satin; silk velvet; silk thread; gold-wrapped paper thread; double twisted silk thread; paper rolls; 125 x 108 cm

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon (Inv. 3407)

Photo © José Pessoa

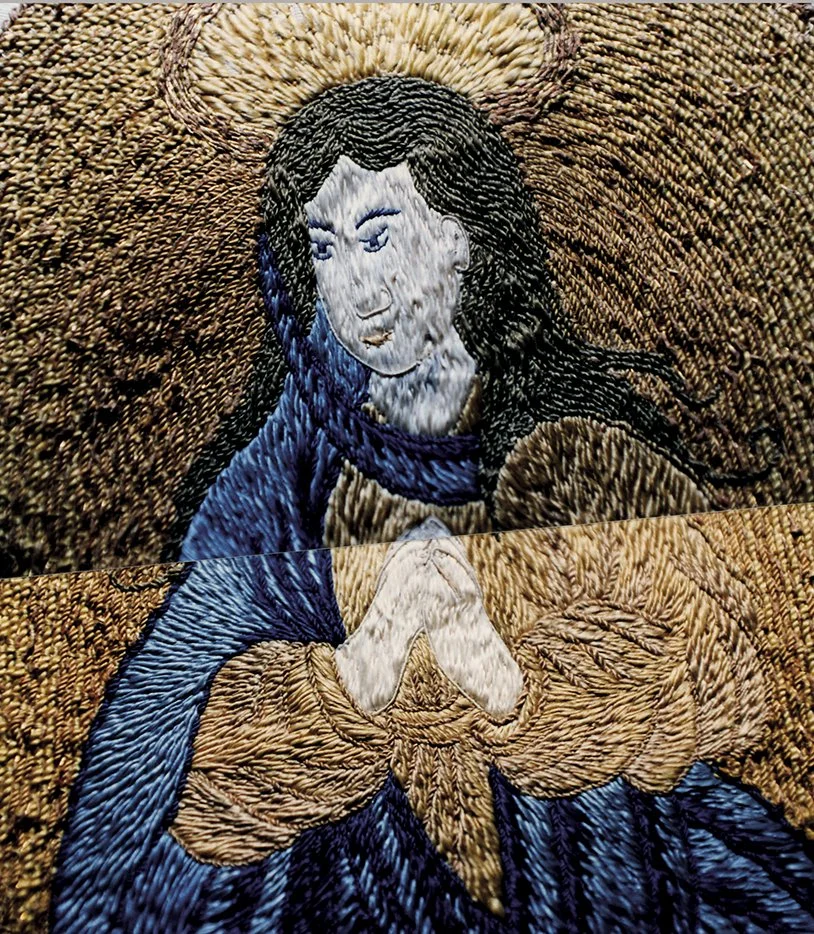

Fig. 6 Sinicized face of the Virgin, detail of a chasuble

China; 1st half of 17th century

Silk satin; silk thread; vegetal thread with silk thread around; gold-wrapped paper thread; 109 x 89.5 cm

Igreja de São Pedro de Miragaia, Porto

Photo © Maria João Ferreira

This vegetal and animal repertoire provides a framework for most of the subjects identified in the pieces studied in the larger survey, which also include Christian, heraldic, and mythological iconography. These objects present a great variety of subjects, even within the Christian framework, showing the vitality and modernity of the Chinese textiles exported to the Portuguese all over the world and the ways in which certain artistic models were adopted over time, in tune with the evolution of taste in Europe. This is particularly evident in the 16th- and 17th-century pieces, in comparison to those of the 18th century, at which point figurative subject matter practically disappeared from liturgical textiles, giving way to vegetal and geometric decorations that embody the power of ornament and its allegorical dimensions.

This change also extends to the technical and material criteria that characterize such pieces over these two chronological periods. Earlier, when production was mainly targeted at the Portuguese, the pieces were made with Chinese materials, with high relief and textured effects achieved through the use of padding materials, like hemp fibres or paper rolls. However, over time, most of the gold-wrapped paper thread was replaced by silk, and the relief effect and double-twisted silk thread—so characteristic of 17th-century Chinese export production—disappeared, giving rise to an international mode of production more suitable to all the East India trading companies that started to negotiate directly with the Chinese following the Kangxi decree of 1685. An example from the first period is a chasuble with an orphrey decorated with a candelabra motif, topped by Christian imagery, with Saint Dominic inserted in an architectural framework on the front and, on the back, the Virgin and Child within an oval medallion circumscribed by a rosary (Fig. 5). In this and many other examples, familiar and standardized attributes and physical characteristics enable the figures’ identification even though they are portrayed with sinicized facial features (Fig. 6).

Fig. 7 Chalice veil

China; 1st half of 18th century

Silk satin; silk thread; 71.5 x 70.5 cm

Igreja de Nossa Senhora dos Mártires, Arraiolos (Inv. AR.SM.1.024 par)

Photo © Carlos Pombo

Fig. 8 Chasuble

China; c. 1750

Silk satin; silk thread; 106 x 69 cm

Igreja de Santa Maria do Bispo, Montemor o Novo (MN.MA.1.014/1 par)

Photo © Carlos Pombo

Chinese artisans did sometimes appropriate or misinterpret themes that they did not always understand. An example of this is a chalice veil from the church of Nossa Senhora dos Mártires (Our Lady of Martyrs) in Arraiolos (Fig. 7), dating from the first half of the 18th century. The veil’s central motif—the Christogram IHS—was inverted when it was copied, as also happened with the representation of some heraldic elements on the first Portuguese-commissioned porcelain, between the 1510s and 1520s (Matos 2011, vol.I). A Chinese chasuble belonging to the parish church of Santa Maria do Bispo in Montemor o Novo is also worthy of note (Fig. 8); its composition has been associated with another chasuble from the Philadelphia Museum of Art that is classified as Italian (Fig. 9). A comparative analysis of the two reveals how the Chinese artisans kept the original structure and ornaments while reinterpreting the composition. In the Chinese piece, the metal thread gave way entirely to silk, even in the braid-like trimming around its main elements. Further, the iconographic symbols alluding to the Immaculate Conception, represented in gold in the mixtilinear elements—such as the Tower of David, the Porta Coeli (the Gateway to Heaven), the mirror, the fountain, and the cedar of Lebanon—disappeared and gave way to new motifs and patterns. The colours and even the scale of some of the ornaments were also altered.

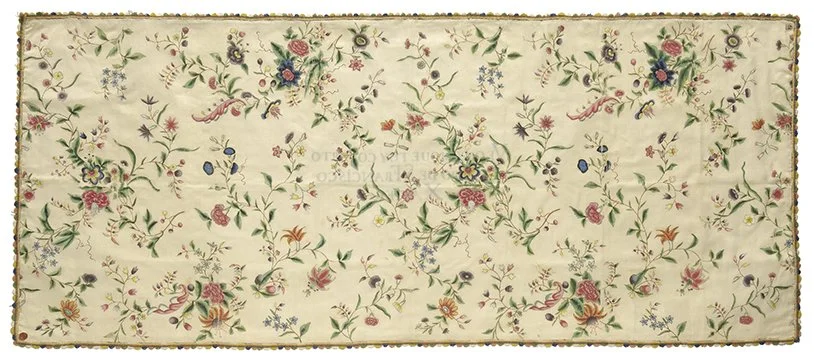

Most of these objects are embroidery on satin and velvet fabrics, but woven and painted fabrics have also been identified. A very complete set of vestments from the Museu de São Roque comprises ten pieces dating from the middle of the 18th century (Fig. 10). The figured fabric displays a patterned structure in orthogonal bands based on a complex compositional scheme of about one metre high, with flowers and foliage in shades of blue, white, salmon, and green on a golden background in gold-wrapped paper thread. The same museum holds a painted coffin veil from around 1770 that was used to cover the body of Saint Francis Xavier in his tomb at the church of Bom Jesus in Goa (Fig. 11). The light ivory gauze fabric is painted with small branches of exotic floral motifs harmoniously distributed over the surface, in line with the decorative patterns of the painted export silks intended for clothing manufacture in Europe.

Fig. 9 Chasuble

Italy; early to mid-18th century

Silk satin; silk thread; silver thread; gilt thread; 125.1 x 73.7 cm

Gift of Archibald G. Thompson and Thomas B. Wanamaker (Jr. 1942-33-12)

Photo © Philadelphia Museum of Art, Collection of Thomas B. Wanamaker

Fig. 10 Dalmatic

China; c. 1750

Figured woven silk with gold-wrapped paper thread; 116 x 78.5 cm

Museu de S.o Roque | Santa Casa da

Miseric.rdia de Lisboa, Lisbon (Ao. 1135)

Photo J.lio Marques

Until recently, these objects were practically ignored or, frequently, interpreted as being from India or other Asian provenances. However, the survey carried out over the last few years has allowed them to be identified as an autonomous group with a very coherent artistic profile, well represented in Portugal. Significantly, a wider survey of objects in foreign museums and private collections has revealed new pieces: many of them identical to, and others traceable to, those identified in Portugal. This is hardly surprising when one bears in mind that, although the Chinese export market was initially aimed at Portuguese tastes, it soon spread to other European recipients, such as the Spanish, the British, and the Dutch, either through Lisbon or directly from Asia. The continuation of this research is bound to bring pleasant surprises in the future.

Maria João Ferreira is curator at Museu de São Roque, Lisbon.

Fig. 11 Coffin veil

China; c. 1750

Silk gauze; painting; lining; 73 x 173 cm

Museu de S.o Roque | Santa Casa da Miseric.rdia de Lisboa, Lisbon (Rel. 247)

Photo J.lio

Selected bibliography

Ana Claro and Maria João Ferreira, ‘Chinese Textiles for the Portuguese Market: Rethinking their History through Dye Analysis’, The Textile Museum Journal 47 (2020), 109–35.

Gaspar Correia, Lendas da India, vol. 1, Lisbon, 1858.

Maria João Pacheco Ferreira, ‘Asian Textiles in the Carreira da Índia: Portuguese Trade, Consumption and Taste, 1500–1700’, Textile History 46, no. 2 (2015), 147–68.

—, ‘Chinese textiles for Portuguese Tastes’, in Amelia Peck, ed., Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500–1800, New York, 2013, pp. 46–55.

—, ‘Chinese Textiles in Christian Contexts in Sixteenth Century India’, CIETA - Bulletin, 86–87 (2009–2010): 40–48.

—, As Alfaias Bordadas Sinoportuguesas (Séculos XVI a XVIII), Lisbon, 2007.

—, Os têxteis chineses em Portugal nas opções decorativas sacras de aparato (séculos XVI-XVIII), 2 vols., Porto, 2011 (phD Thesis). Available in: https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/handle/10216/56346

Maria Antónia Pinto Matos, The RA Collection of Chinese Ceramics: A Collector’s Vision, 3 vols., London, 2011.

Paula Monteiro, Ana Claro, Cristina Dias, and António Candeias, ‘Fragmentos da indumentária fúnebre do arcebispo Dom Gonçalo Pereira: Entre lampassos, bordados e passamanaria’, in Begoña Farré Torras, ed., Actas do IV Congresso de História da Arte Portuguesa em Homenagem a José-Augusto França Sessões Simultâneas, 2nd ed., Lisbon, 2014, 87–93.

Siro Ulperni, O Forasteiro Admirado. Relaçam Panegyrica do Trivnfo, e Festas, que Celebrou o Real Convento do Carmo de Lisboa pela Canonização da Seráfica Virgem S. Maria Magdalena de Pazzi, Religiosa da sua Ordem, primeira parte, Lisbon, 1672.

This article featured in our Jul/Aug 2022 print issue.

To read more of our online content, return to our Home page.