Chronicles of Contact: Early Composite Rubbings from Zhang Tingji’s Writings on Collected Antiquities in the Pavilion of Tranquil Manner

Angela Sha

Perhaps touch is not just skin contact with things, but the very life of things in the mind?

—Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media (italics in original)

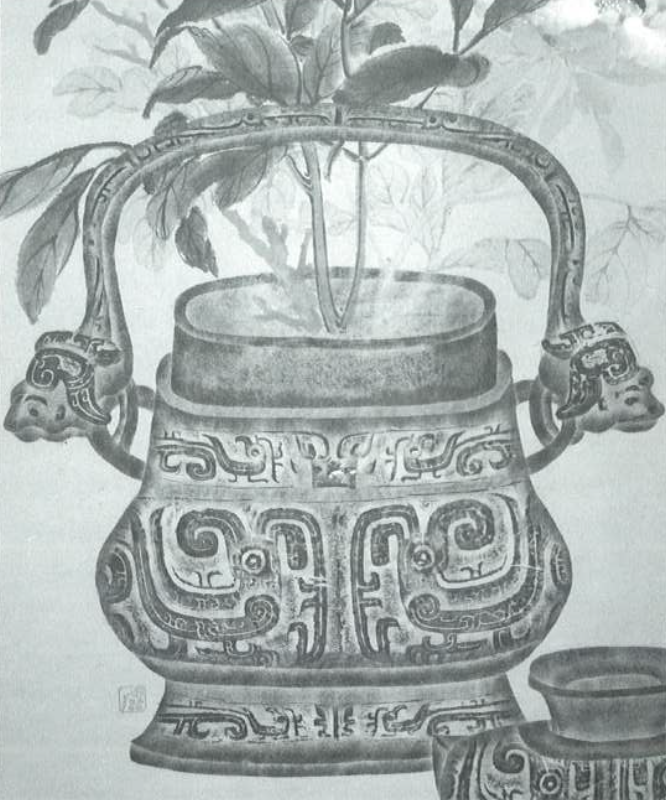

1. Rubbings from Bronzes with Painted Flowers

By Lin Fuchang (d. after 1877); c. 1860

Ink and colour on paper; 119 × 45.6 cm

Weng Family Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Photo © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The composite or full-form rubbing (quanxing ta) emerged in response to the methodological imperatives of antiquarianism in the late 18th to early 19th century of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). The pursuit of precision—a byproduct of China’s engagement with Western science and indigenous intellectual movements—infiltrated the century’s antiquarian agenda and its historiography. Bai Qianshen (2010, p. 301) observes that emperor Qianlong’s colossal efforts in 1749 to catalogue bronze vessels from the imperial collection culminated in illustrations more precise than their Song dynasty (960–1279) precedents. As imperially collected antiquities passed into private hands towards the end of Qianlong’s reign (r. 1735–95), the composite rubbing came to constitute a defining medium of its time. Scholars enlisted the ink rubbing, an archaic reprographic technique used to record inscriptions or engravings on two-dimensional surfaces, to their contemporary calling of rendering objects in the round with precision.

2. Detail from figure 1 showing a rubbing of a Western Zhou you vessel

(After Bai, 2010, p. 297)

The rubbing of a Western Zhou you vessel, once owned by the prominent 19th-century collector Wu Yun (1811–83), from a painting of ‘antiquities and flowers’ (bogu huahui) by Lin Fuchang (d. after 1877) typifies the composite rubbing (figs 1 and 2). A sharp charcoal border delineates the vessel’s contours. Across the vessel’s body, the illustration’s outline gradates to a lighter grey to blend with the pigment of the ink rubbing, which extracts an impression of an incised or slightly raised surface. The rubbing in Lin’s painting, then, is composite for its synthesis of multiple surfaces into a single image while presenting the illusion of three-dimensional form. Several instances of rubbing make up the composite whole: three zoomorphic bands on the vessel’s foot, body, and neck; two ram’s heads on the sides of the handle; and the handle itself, which bears a decorative pattern. Each elaboration of the vessel’s surface is delimited by crisp outlines—nothing spills over. The vessel’s opening, suggested through shading, indicates an interior space and extends the illusion of the image’s volumetric form. Such an image hybridizes the operations of rubbing and painting to mark the composite rubbing.

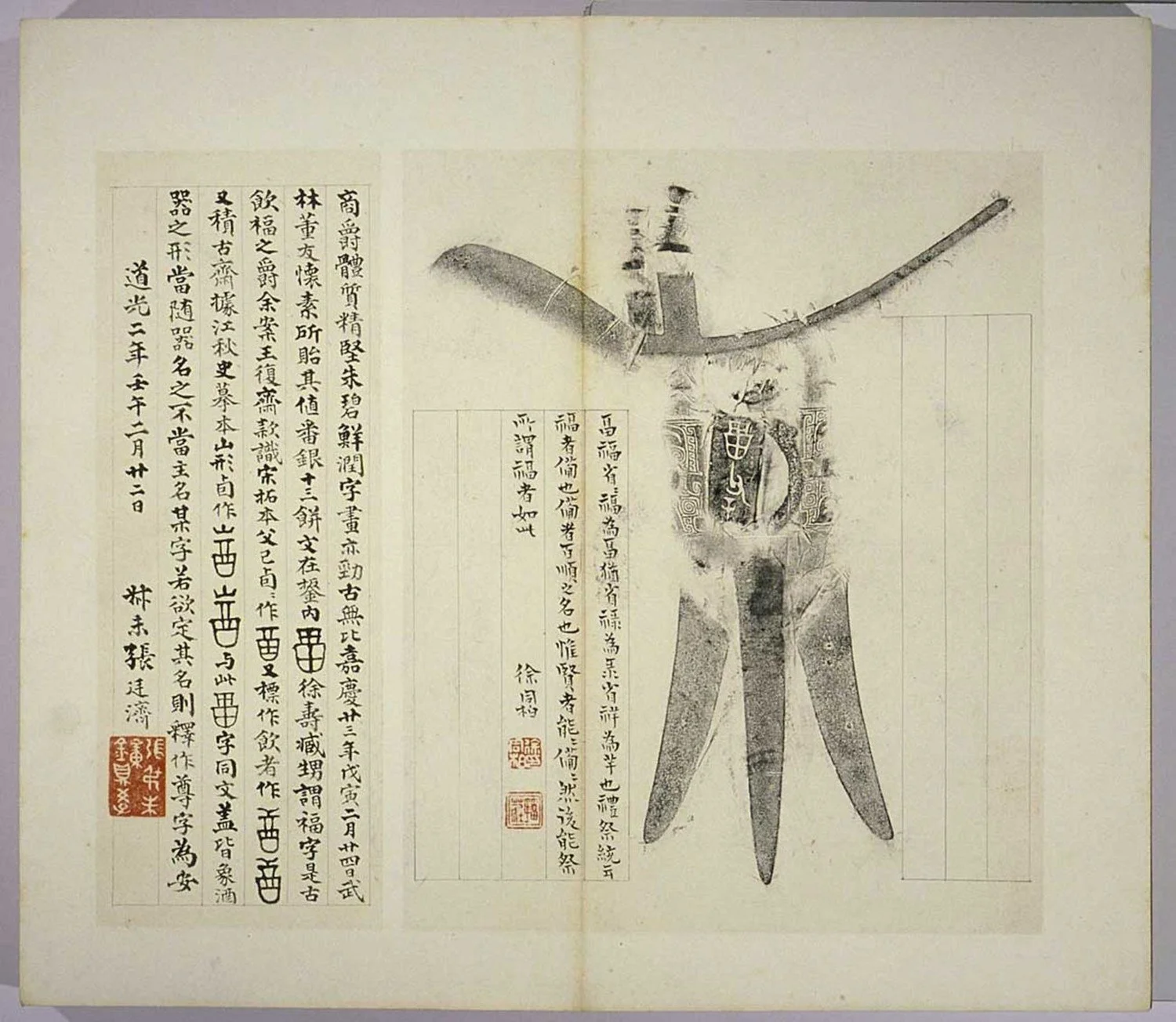

3. ‘Rubbing of a Western Zhou gui vessel’ in Writings on Collected Antiquities in the Pavilion of Tranquil Manner (Qingyige suocang guqiwu wen)

By Zhang Tingji (1768–1848); c. 1813

Ink rubbing on paper; dimensions unknown

Kyoto University, Kyoto

(After Tang, 2020, p. 7)

Far from visually homogenous, the composite rubbing encompassed a multitude of forms during its first century of evolution. Among the early efforts in this tradition were rubbings compiled by Zhang Tingji (1768–1848) in his antiquarian catalogue, Writings on Collected Antiques in the Pavilion of Tranquil Manner (Qingyige suocang guqiwu wen; hereafter Collected Antiquities), produced during the first two decades of the 19th century and reprinted in 1925. Despite its artistic and documentary significance, Zhang’s catalogue has been the subject of particular castigation in art historical scholarship. To Thomas Lawton, the rubbing of a Western Zhou gui vessel in Zhang’s catalogue appears amiss and evinces a certain inchoateness (figs 3 and 4) (Lawton, 1995, p. 10). Though it assembles multiple decorative bands into an image, it disregards three-dimensional form, reverting to the one-dimensional rubbings of steles practised since the 6th century. The impression faithfully replicates what Wu Hung described as ‘a manufactured skin peeled off the object’ but hesitates to divulge the vessel’s shape (Wu, 2003, p. 30). There is no indication of an opening, and no outline to signal where the vessel’s body ends. Its two frail handles barely attach, their presence almost spectral. In Lawton’s words: ‘While not so successful as later rubbings of this type, the examples in [Collected Antiquities]—still essentially one dimensional—display a sensitivity to formal variations that signal a marked improvement on traditional line drawings’ (Lawton, 1995, p. 10). The famed archaeologist Rong Geng, in his 1941 study of ancient bronzes, expressed similar reservations in harsher terms, describing Zhang’s rubbings as technically insufficient, ‘all of them lacking in craft’ (‘jun bu shen gong’) (quoted in Tang, 2020, p. 7).

4. Western Zhou Zhongfu fugui vessel with later wooden lid and stand

Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–771 BCE); c. 11th–10th century BCE

Bronze, wood, jade; dimensions unknown

Private collection

Photo © Sotheby’s

These assessments of Zhang’s rubbings soon become suspect. Ruan Yuan’s (1764–1879) Studio for Accumulating Antiquities (Jigu tu) from 1803, the first extant scroll to represent a collection in rubbing, similarly strips the skin of its objects in the round (fig. 5)—Zhang’s rubbing, rather than an anomaly, has found its kin. A sustained engagement with rubbings from Collected Antiquities, particularly that of the Western Zhou gui vessel, extricates the composite rubbing from the teleological end of precise, three-dimensional representation. Rather than viewing early composite rubbings as impoverished images on their course to maturation, I contend that they first developed in concert with the representational needs of Evidential Learning (kaozhengxue or kaojuxue) and visualized haptic engagement. Key to the rubbing’s functioning were moments of interrupted movement during its creation, where the ink failed to register—in other words, the image’s insufficiencies and absences. In doing so, I follow Michael Hatch’s revelatory monograph on the inflated importance of ‘tactility’ in mid-Qing Chinese art, though I adopt the term ‘haptic’ to underline the imbrication of senses that is the very precondition of physical contact. As Marshall McLuhan put it a century later: implied in the momentary encounter with things—here between the antiquarian and the vessel—is a kind of contact that extends beyond the physical to reach the cognitive (McLuhan, 1994, p. 108).

5. ‘Rubbings of Inscriptions from Bronze Bells’ in Studio for Accumulating Antiquities (Jigu tu)

By Ruan Yuan (1764–1879); c. 1803

Ink rubbing on paper; dimensions unknown

National Library of China, Beijing

(After Eric Lefebvre, ‘L’“Image des antiquités accumulées” de Ruan Yuan: La representation d’une collection privée en Chine à l’epoque pré-moderne,’ Arts Asiatiques 63 (2008): 65)

The parallel histories of Evidential Learning and antiquarianism during the mid-Qing have been repeatedly rehearsed, and central to understanding Collected Antiquities is the epistemological value vested in material objects. Ming dynasty (1368–1644) intellectual precursors of the Evidential Learning movement asserted the value of the fact. If knowledge can be partitioned into moral and factual knowledge like the Neo-Confucians maintained, then late Ming scholars presaged the ascendancy of Evidential Learning through their embrace of the latter. Their preference for knowable facts reached fruition in the mid-Qing, as Evidential Learning, centred in the lower Yangzi River region, became the dominant intellectual current. In remaking their epistemological fabric, evidential scholars reacted against the hegemony of Neo-Confucian thought from the Song to the Ming, which, in valorising moral learning, left the Confucian Classics vulnerable to excessive interpretation. Concerned that the Classics had mutated over centuries of transmission, they turned to philology and hoped, in Benjamin Elman’s words, that ‘through the power of the scholar’s exegetic labours, the original forms of texts could likewise be restored’ (Elman, 1984, p. 28).

For antiquarians, the fact materialized in the object. Nowhere is the intellectual debt that Qing antiquarians owed to Evidential Learning more apparent than in their travels to ancient monuments in person (fangbei), a practice that peaked during the reigns of emperors Qianlong and Jiaqing (r. 1796–1820). Like evidential scholars, who eschewed interpretive texts in favour of direct exegetical readings of the Classics, Qing antiquarians sought to verify epigraphic material by visiting stone steles at their original sites. Their search for stele fragments and other antiquities took them to remote locales across the empire. Chu Jun (act. 18th century), for one, insisted on travelling to stone steles himself while compiling his illustrated catalogues of antiquities (Tseng, 2010, p. 280). Whereas many antiquarians during the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127) were content to study inscriptions from reproductions, Qing scholars, distrustful of knowledge imparted through print, authenticated inscriptions through empirical experience. In doing so, Qing antiquarians positioned themselves at the centre of knowledge production. The early Qing polymath Gu Yanwu (1613–82), upon visiting a Ming dynasty stele in the mountains, found relief in knowing that his documentation would ‘ensure that future generations can trust antiquity’ (quoted in Brown, 2011, p. 27). For evidential scholars and antiquarians alike, material traces of the past, whether in the form of stone steles or bronze vessels, physically incarnated what was so desirable about factual knowledge.

In search of a reliable means to document material fact, mid-Qing antiquarians conscripted the rubbing to illustrate antiquarian catalogues. The technique consists of affixing a piece of paper to a surface with an adhesive, moulding the paper to the surface’s form, and then applying ink through tapping motions. The pigment latches onto the raised parts of the surface, leaving any sunken inscriptions in the negative (Wu, 2003, pp. 46–47). Lillian Tseng understands Chu Jun’s rubbings of ancient monuments as Peircean indexical images, where the sign is tethered to the thing signified through physical contact (Tseng, 2010, p. 278). By authenticating ancient monuments and extracting rubbings from their weathered surfaces, Chu Jun established himself as a point of contact between the present and antiquity. The authority of Chu’s replication derived from his presence as a physical witness—reminiscent of evidential scholars such as Gu Yanwu, who, by travelling to remote sites, sought proximity to the matter on which textual sources were carved. As indices of antiquity, rubbings came to be valued by mid-Qing antiquarians for their ability to translate the material legacy of antiquity into a portable image through touch.

6. ‘Rubbing of a Han Washbasin’ reproduced in print by Bao Changxi in Fragments of Bronze and Stone (Jinshixie) (1876-7)

By Ma Qifeng (1800–62); c. 1858

Ink on paper; dimensions unknown

(After Lu, 2020, p. 4)

Much of the scholarship on composite rubbings sketches an uncomplicated history: the technique purportedly emerged around the late 18th century at the hands of the relatively obscure Ma Qifeng, whose only extant rubbing of a Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) washbasin from 1798 survives in a printed reproduction (fig. 6). Only in recent years has Chinese-language scholarship begun to erode the notion of invention (see the special issues of Zhongguo shuhua and Xiling yicong). Equipped with a new understanding of Ma’s biography, Lu Leiping not only corrects the earlier misdating of the 1798 rubbing, which was likely produced in 1858, but also retreats from an evolutionary model that emphasizes the identification of origins (Lu, 2020, p. 10). Past scholarship has generally magnified the achievements of the monk Dashou (1791–1858), also known as Liuzhou, who popularized the composite rubbing’s integration into painting and expanded its function beyond replication (see, for example, chapter 4 of Hatch, 2024). To elevate a single figure as pioneering the composite rubbing, however, misrepresents the fundamentally collective nature of its appearance in the Zhejiang region, where it emerged not in isolation but as a technique developed in concert with the representational needs of evidential scholars.

7. ‘Rubbing of a Shang dynasty jue vessel’ in Writings on Collected Antiquities in the Pavilion of Tranquil Manner (Qingyige suocang guqiwu wen)

By Zhang Tingji (1768–1848); c. 1813

Ink rubbing on paper; dimensions unknown

Kyoto University, Kyoto

(After Tang, 2020, p. 6)

The first volume of Zhang Tingji’s Collected Antiquities, named after his ‘Pavilion of Tranquil Manner’ in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province, selectively documents vessels in composite rubbing: of the 41 bronzes collected, only the Western Zhou gui vessel, four jue vessels, and three bells were recorded using the reprographic technique (fig. 7) (Tang, 2020, p. 7). An 1804 exchange between Zhang and Qing official and fellow antiquarian Weng Shupei (1765–1811) mentions the term ‘composite’ (quanxing) in describing the rubbing, situating Zhang Tingji within technique’s early history (Wang, 2020, pp. 21). Sang Shen, tracing the genealogy of the composite rubbing, identifies three distinct phases in its evolution and affirms its winding developmental trajectory. Only in the second phase did composite rubbings acquire a sensitivity to three-dimensional representation, and Sang characterizes rubbings from the first phase as inattentive to perspective and uneven in their application of ink (Sang, 2004, p. 34). Take Zhang’s rubbing of the Western Zhou gui vessel (see fig. 3), produced around 1813, as an example of the alleged crudeness of early composite rubbings (Tang, 2020, p. 7). Speckles of obsidian pigment cluster at the base of the vessel’s body and dissipate into its torso. These flecks of colour likely reflect the natural freckles of an aged bronze vessel—areas of corrosion that Zhang or his rubbing maker preferred to leave untouched. Sang hypothesizes that the uneven colouring of the early composite rubbing resulted from the corroded surface of ancient vessels, an effect that later substitutes such as wooden engravings could not have replicated (Sang, 2004, p. 35). The two decorative bands in Zhang’s rubbing, furthermore, lack the legibility that the antiquarian expects in an image; only upon close inspection can one decipher their basic components. The handle on the left suffers most from visual obscurity, its zoomorphic head reduced to an amorphous mass.

Zhang’s composite rubbings share a number of characteristics with other early examples, but it would be mistaken to subscribe to a segmented chronology that overlooks the coexistence of different approaches. In referring to Collected Antiquities as an example of early composite rubbings, I intend less to recapitulate a linear understanding of their development than to insist that certain formal characteristics of Zhang’s rubbings were in recession by the mid to late 19th century, when Lin Fuchang’s rubbing of the Western Zhou you was made. That different approaches to making composite rubbings were present from the very beginning is most apparent in Zhang’s 1830 inscription from a scroll of a Zhou dynasty jue vessel:

After I acquired this jue, Chen Shuyuan cut sheets of paper, each with a separate rubbing, and pieced them together to create an image, mounting it to decorate the scholar’s room. […] Zhang Shouzhi prepared an entire sheet of paper to make a fine rubbing, refraining from connecting the vessel’s different components and arriving at a natural composition. The image’s dimensions, whether its length or width, differ little from the original vessel. Zhang’s rubbing far exceeds Chen’s pieced-together rubbing. Just facing this image, one can endlessly admire it.

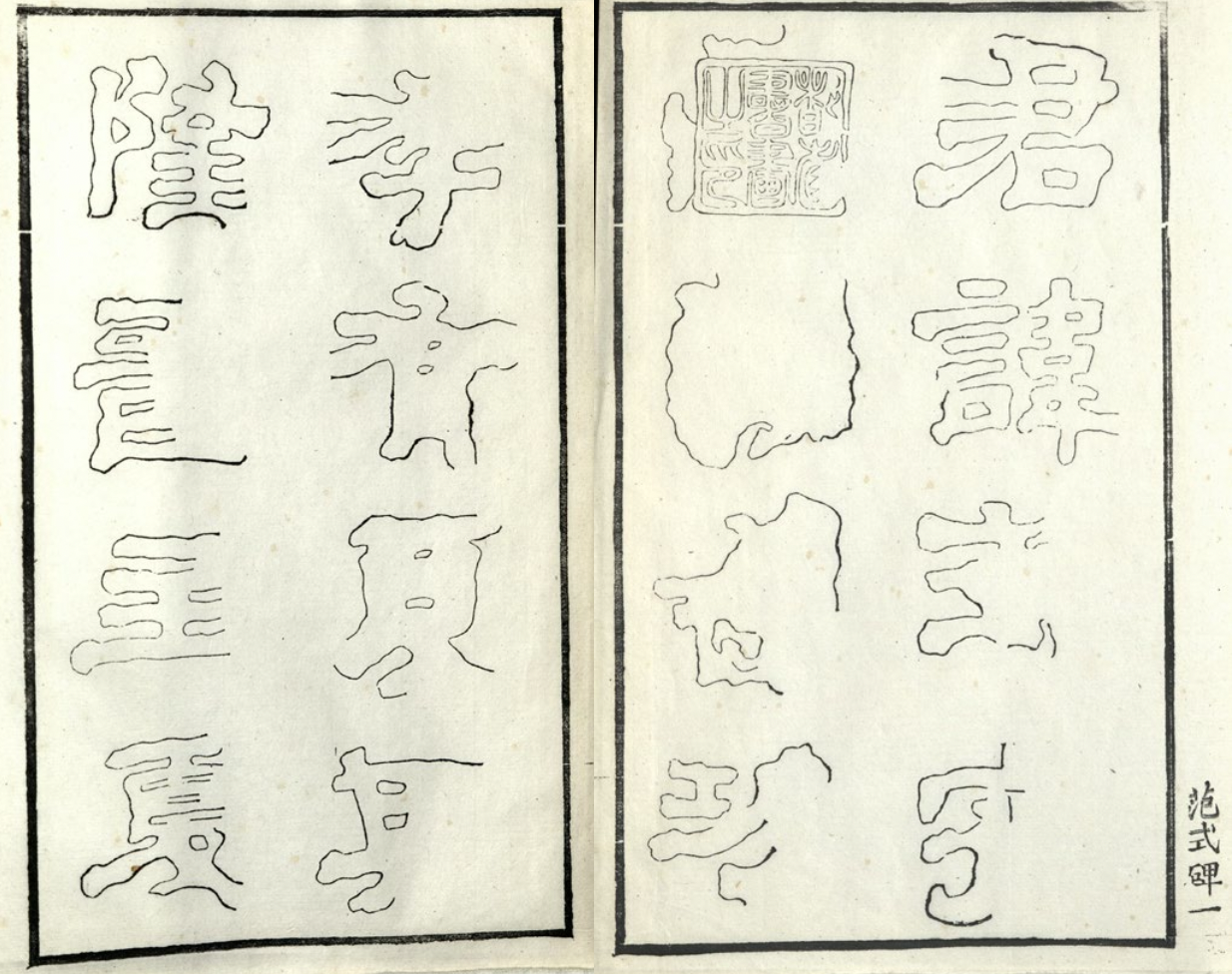

(Quoted in Tang, 2020, p. 11; translated by the author)

Here, Zhang recounts his purchase of the vessel in 1819 and contrasts the two techniques used by the rubbing makers Chen Shuyuan and Zhang Shouzhi. The former took a separate rubbing from each anatomical part of the vessel and constructed the composite whole through a process of assemblage, a method for which the Qing antiquarian Chen Jieqi (1813–84) would later become known. Zhang Tingji preferred Zhang Shouzhi’s process, one less manicured and free of the artifice that he felt spoiled Chen’s rubbings. It is precisely this aversion to mediation that situates Zhang Tingji’s rubbings alongside other mid-Qing epigraphic material. Huang Yi’s (1744–1802) Engraved Texts of the Lesser Pavilion (Xiao Penglaige jinshi wenzi) from 1800 similarly sought to preserve the object’s materiality as it migrated from rubbing to print (fig. 8). Initially compiled as a collection of rubbings of ancient inscribed steles, the catalogue was later reproduced in print by modifying a technique used to faithfully copy calligraphy. The result of Huang’s translation from rubbing to print, observes Michael Hatch, forsakes the legibility of the text for the materiality of the stone: ‘thin, discontinuous lines exactly traced the ruined shapes recorded in the rubbings and, by extension, the original worn topography of the stones’ (Hatch, 2024, p. 53). Underlying Huang’s painstaking efforts to express the rubbing’s blurred contours in print was his desire to minimize the mediation between the ancient monument and his readership—a decision to avoid unnecessary intervention also present in Zhang’s composite rubbings.

8. ‘Reproduction of the Fan Shi Stele rubbings’ in Engraved Texts of the Lesser Penglai Pavilion (Xiao Penglaige jinshi wenzi)

By Huang Yi (1744–1802); c. 1800

Woodblock print on paper; height 31 cm

Thomas J. Watson Library, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

(After Michael J. Hatch, “Outline, Brushwork, and the Epigraphic Aesthetic in Huang Yi’s

Engraved Texts of the Lesser Penglai Pavilion (1800),” Archives of Asian Art 70, no. 1

(April 2020): 24)

To be sure, Zhang Tingji’s preferred method of rubbing still belied a contrived process of making. Bai Qianshen explains that the rubbing maker had to adjust the vessel to create sectional rubbings of its components and fill in any gaps (Bai, 2010, p. 295). Zhang’s rubbing of the Western Zhou gui vessel likely followed a similar process (see fig. 3). The interrupted lines of the decorative bands betray that Zhang had to reposition the paper multiple times to accommodate the object in the round. The image only feigns a continuous process of making, the effect of skin stripped from a body. Yet it is precisely these formal inadequacies—from the image’s diffuse patterns to its barely attached handles—that work to preserve the vessel’s materiality and, by extension, ‘the tactile delight that scholars experienced when they handled artifacts’ (Brown, 2011, p. 65). The impression’s hurried trace translates the rubbing maker’s movement in the making of the image and visualizes the antiquarian’s physical handling of the vessel. Leaving the image’s visual interstices intact, Zhang Tingji bartered the object’s structural clarity for its material immediacy. The sight of the unpolished rubbing would have reassured the antiquarian that the material fact was indeed there, and by reproducing its textures, the image encourages viewers to envision the vessel’s presence in its absence.

An appreciation of the early composite rubbing for its visual registration of the antiquarian’s contact with the vessel dislodges the teleology of the technique’s development as careening toward precise, three-dimensional representation. It also departs from the discouraging verdicts of Thomas Lawton and Rong Geng, who saw Zhang’s rubbings as fundamentally lacking, yet to ripen into a later rubbing like Lin Fuchang’s Western Zhou you vessel. Through immortalizing a moment of touch, Zhang’s rubbings gesture beyond, in McLuhan’s words, the antiquarian’s ‘skin contact with things’ and towards a cognitive possession of antiquity, which the mid-Qing found ever so fugitive. The partial, fragmentary image elicits in the viewer a kind of haptic imagination—where the experience of seeing the impression intertwines with that of caressing the vessel and making the rubbing. In other words, what some scholars found wanting in Zhang Tingji’s composite rubbing was precisely what permitted the mid-Qing antiquarian to access the material traces of antiquity, even in the absence of the vessel itself. The early composite rubbing narrowed the antiquarian’s distance from the past better than any full representation ever could.

Angela Sha studies at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU and is a Research Assistant at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Selected bibliography

Bai Qianshen, ‘Composite Rubbings in Nineteenth-Century China: The Case of Wu Dacheng (1835–1902) and His Friends’, in Wu Hung, ed.,

Reinventing the Past: Archaism and Antiquarianism in Chinese Visual Art and Culture, Chicago, 2010, pp. 291–319.

Shana J. Brown, Pastimes: From Art and Antiquarianism to Modern Chinese Historiography, Honolulu, 2011.

Benjamin Elman, From Philosophy to Philology: Intellectual and Social Aspects of Change in Late Imperial China, Cambridge, MA, 1984.

Michael Hatch, Networks of Touch: A Tactile History of Chinese Art, 1790–1840, Philadelphia, 2024.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1994.

Thomas Lawton, ‘Rubbings of Chinese Bronzes’, Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 67 (1995): 7–48.

Lu Leiping, ‘Zhehe diqu zaoqi quanxing chuanta qunti jiqi yingxiang’, Xiling yicong 12 (2020): 4–19.

Sang Shen, ‘Qingtongqi quanxingta jishu fazhan de fenqi yanjiu’, Dongfang bowu 12 (2004): 32–39.

Tang Youbo, ‘Cong qingyige tongqi taben kan zaoqi quanxingta’, Xiling yicong 7 (2020): 5–19.

Lillian Tseng, ‘Between Printing and Rubbing: Chu Jun’s Illustrated Catalog of Ancient

Monuments in Eighteenth-Century China’, in Wu Hung, ed., Reinventing the Past: Archaism and Antiquarianism in Chinese Visual Art and Culture, Chicago, 2010, pp. 255–90.

Wang Yanming, ‘Qingyige yu zaoqi quanxingta’, Xiling yicong 12 (2020): 20–26.

Wu Hung, ‘On Rubbings: Their Materiality and Historicity’, in Judith Zeitlin and Lydia Liu, eds., Writing and Materiality in China, Cambridge, MA, 2003, pp. 29–72.