‘An Oriental Kiosk’: The Building of the ‘Arab Hall’ at Leighton House in London

Melaine Gibson

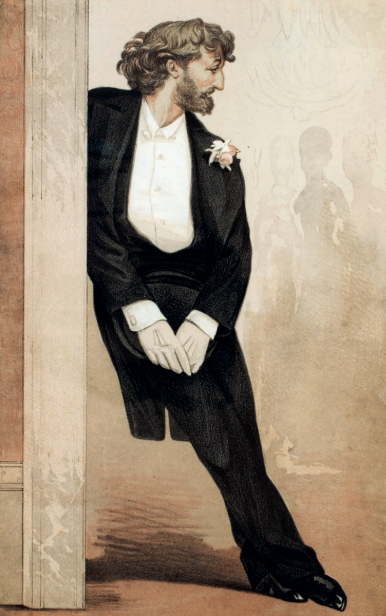

Fig. 1 Portrait of Frederic Leighton By Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836–1902) for the magazine Vanity Fair, 29 June 1872 Lithograph on paper, 36.5 x 24.5 cm Leighton House, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London (acc. no. LH1773)

Standing at 12 Holland Park Road in London is Leighton House, formerly the home and studio of the British artist Frederic Leighton (1830–96) (Fig. 1). Although the red brick exterior resembles the buildings around it, the interior is quite unique. In addition to a large studio on the first floor, the house features an extension with a central fountain and tiled walls that recreates the type of reception room found in 19th century Damascus or Cairo, as well as other details inspired by Islamic architecture and design. This article tells the story of the collaboration between Leighton, the architect George Aitchison (1825–1910) and artists such as Walter Crane (1845– 1915) and William De Morgan (1839–1917) to create the house and its remarkable ‘Arab Hall’. A public museum since the 1920s, the house is now in the final phase of a conservation project to recreate its appearance at the time of Leighton’s death.

A painter and sculptor of historical and classical subjects, Frederic Leighton achieved fame and success at a young age. His large painting Cimabue’s Sacred Madonna Carried in Procession through the Streets of Florence, completed in Rome in 1855, was considered one of the best pictures of the year at the Royal Academy of Arts in London and subsequently caught the attention of Prince Albert and Queen Victoria, who bought it for the considerable sum of 600 guineas (approximately £83,000 in today’s currency). Leighton spoke several languages as a result of his upbringing and education in various European countries, and clearly enjoyed travelling. He had his first experience of the Middle East as a young man of 27, when he went to Algeria. The visit made a deep impression on him; more than twenty years later, he recalled in a letter how he had loved ‘the East’ from that moment on (Barrington, 1906, vol. 1, p. 301). It was his custom to set off in the autumn and in the years before 1878, when he was elected president of the Royal Academy, he travelled widely across both Europe and the Middle East.

Leighton was an inveterate collector, and sometimes mentioned the acquisitions he made in his letters home. In 1867, while on the island of Rhodes in Greece, he acquired a collection of what he described as ‘beautiful specimens of old Persian faience (Lindos ware), chiefly plates’ (Barrington, 1906, vol. 2, p. 129). He was assisted in this purchase by the British consul Alfred Biliotti (1833–1915), who was closely involved in archaeological projects on the island alongside Auguste Salzmann (1824–72), a French archaeologist and photographer. Biliotti would have been familiar with dealers trading in socalled ‘Lindos ware’ because over the previous years Salzmann had accumulated a very large collection, which was eventually acquired by the Musée de Cluny in Paris. Leighton, like every other collector of this period, was under the misapprehension that the pieces he was buying were produced by exiled Persian potters in Lindos, a village on the island, although we now know that they were manufactured in Iznik in Turkey in the second half of the 16th and early 17th centuries.

In 1868, a year after his long trip to Greece, Austria and Turkey, Leighton travelled to Egypt bearing a letter from the Prince of Wales that secured him an introduction to the Ottoman viceroy Ismail Pasha (1830–95), who provided him with a royal steamer for his trip up the Nile. Although he kept a fairly detailed account of his impressions and activities on this trip, he does not mention any purchases. However, he did withdraw £50 (the equivalent of £3,000 today) from his bank account, presumably to fund an acquisition or two. A famously charming man, Leighton always sought out long-term British residents at the places he visited. When he went to Damascus in 1873, he befriended Reverend Dr William Wright (1837–99), a Presbyterian missionary who helped him buy ‘oriental draperies’ and yet more ‘Persian faience’ (Wright, 1896, p. 184).

Fig. 2a (left) Window with the words ‘Ya Allah’ (‘Oh Allah’) and a vase of flowers Egypt(?), c. 1800–70

Wood, plaster and glass, 97.6 x 61 cm

Leighton House, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London

Fig. 2b (right) Window with the words ‘Ya Muhammad’ (‘Oh Muhammad’) and a vase of flowers Egypt(?), c. 1800–70

Wood, plaster and glass, 98 x 60.5 cm

Leighton House, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London

Leighton’s many new acquisitions, which in addition to textiles, carpets and ceramics included turned-wood openwork window screens known in Arabic as mashrabiyya and stained-glass windows called qamariyya, were eventually installed in his new house in London. In 1864, he had bought a plot of land on Holland Park Road and asked the architect George Aitchison, an old friend he had met in Italy, to draw up plans. During their thirty-year collaboration, Leighton was so closely involved in the house’s construction and decoration that Aitchison is said to have commented: ‘Every stone, every brick— even the cement—no less than all the wood and metalwork passed under his personal observation’ (Staley, 1906, p. 69).

Fig. 3 View of the tiled wall at the base of the stairs of the main house, with seat made from a 17th–19th century Syrian chest in the foreground, Leighton House, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London

The original design was for a red brick building with a large studio on the upper floor. Over the following years, several alterations and enlargements were made and some of the pieces Leighton had purchased on his trips to Rhodes, Cairo and Damascus were incorporated. The east end of the studio was remodelled in early 1870 after Leighton was elected a full academician at the Royal Academy. Aitchison installed two of the stained glass windows called qamariyya (Figs 2a and 2b) into the eastern wall of an extension to the studio and produced a signed watercolour of his design dated 15 February 1870 (Library of the Royal Institute of British Architects, acc. no. SB93/4 (1-2); Dakers and Robbins, 2011, p. 105). Leighton may have acquired the windows during his Cairo trip in 1868; both are in wood frames with plaster compartments set with coloured glass and are decorated with a vase of flowers beneath an inscription, one reading ‘Ya Allah’ (‘Oh Allah’) and the other ‘Ya Muhammad’ (‘Oh Muhammad’), suggesting that the windows may originally have come from a mosque or another religious building.

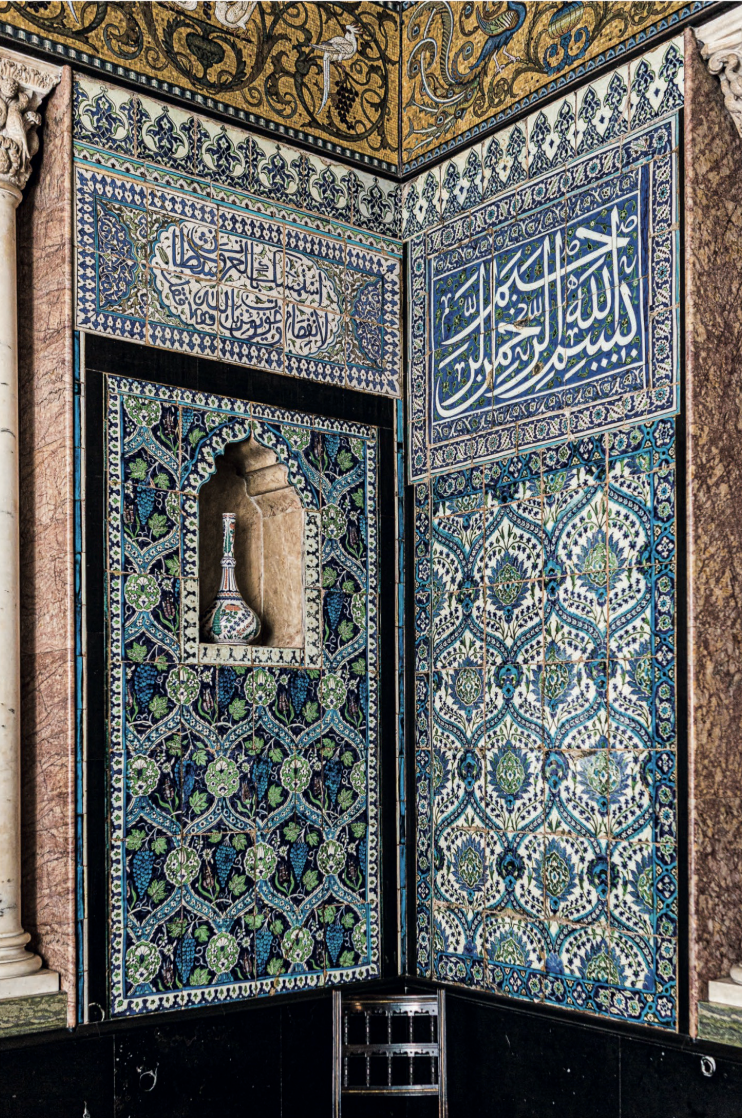

Fig. 4 Panel of tiles with the bismillah, the opening phrase of each chapter of the Quran Syria, Damascus, c. 1550–1650

Stone paste with underglaze painted decoration, 85 x 119 cm Leighton House, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London

A significant change to the house, possibly made around this time, was the enlargement and reorganization of the ground floor. An arrangement of tiles that can be identified as having been produced in Turkey was set onto the northern wall at the bottom of the stairs (Fig. 3). Four different tile patterns, the most distinctive being a flower vase flanked by cypresses, but all painted in tones of blue, turquoise and white, were arranged side by side in two square formations around a central tile painted with the distinctive red, iron-rich clay slip, or ‘Armenian bole’, for which Iznik had become famous from the mid-16th century.

Fig. 5 North elevation of Leighton House showing the Arab Hall Reproduction of an illustration in Building News, 1 October 1880 Original lithograph on paper by James Akerman (act. c. 1875–1906?), dimensions unknown Leighton House, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London

Most of these tiles are not of the highest quality and can be dated to the second half of the 17th century, when the high point of Iznik production was over; they are comparable with examples displayed in the harem area of the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, which was largely rebuilt after a fire in 1666. The pleasure this wall of tiles gave Leighton can be surmised from the placing of a seat directly opposite: carefully constructed from the frame of a 17th–19th century Syrian chest bought in Rhodes (Pepys Cockerell, 1900, p. 96, where it is described as Persian), the seat is made of wood inlaid in ivory and bone with floral designs and an elaborate central shamsa, or ‘sunburst’. The interior is upholstered with embroidered silk cushions. On the seat’s upper ledge is displayed a stuffed peacock with glowing, iridescent tail feathers, the very symbol of the Aesthetic movement, the cult of ‘art for art’s sake’.

A second panel of six tiles was attached to a section of wall under the stairs and, like the larger panels, is visible in an engraving accompanying a brief article on artists’ studios published in the December 1876 issue of Building News. This panel is decorated with the bismillah, the opening phrase of each chapter of the Quran, in a very elegant script on a dark blue ground (Fig. 4). The floral scrolls behind the writing are painted in a vivid green with touches of purple and black, a colour combination associated with Damascus, although there is no way to establish whether Leighton acquired the panel on his 1873 trip to that city, during his 1867 trip, which included Rhodes and Istanbul, or on his 1868 trip to Cairo. By the mid-1870s historical artworks from across the Middle East were being widely traded within the region, and the location in which a piece was acquired is not a secure indication of its origin.

These first ‘oriental’ additions to the house inspired Leighton and Aitchison to devise an even more ambitious plan—the extension to the western end of the house that came to be known as the ‘Arab Hall’, largely accomplished between 1877 and 1879, although not completed until 1881 (Fig. 5). The exterior is built of red brick to a square plan with an octagonal drum supporting a tall dome pierced by eight windows; a row of merlons runs around the parapet exterior and a metal spire topped by a crescent crowns the dome. The interior is decorated with polychrome tiles and mosaic on the walls, marble columns in the recesses, wood mashrabiyya over the windows, painted and gilded friezes around the drum, and gilding on the dome (Fig. 6). The contrast of a simple exterior with a lavish interior is typical of Islamic buildings and was quite intentional. Aitchison makes a point of stating that in Middle Eastern architecture ‘ornamental decorations were reserved for the inside, the people always being afraid of attracting the Evil Eye by any show of wealth, beauty or magnificence’ (Aitchison, 1903, p. 519).

Fig. 6 Interior view of the Arab Hall

Leighton House, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London

Aitchison was very aware of the architectural traditions of the Middle East, his appreciation of its forms and designs no doubt developed during his own journeys around the region. Throughout his life he advocated the use of colour in architecture, a feature he particularly associated with the use of polychrome tile panels (Aitchison, 1884, p. 298). Reminiscing about Leighton shortly after his death, Aitchison refers to the artist’s collection of ‘… lovely Saracenic tiles … stained glass, and lattice-work from Damascus [meaning mashrabiyya] … fitted into an Arab Hall, something like La Zisa at Palermo …’ (Aitchison, 1896, p. 265).

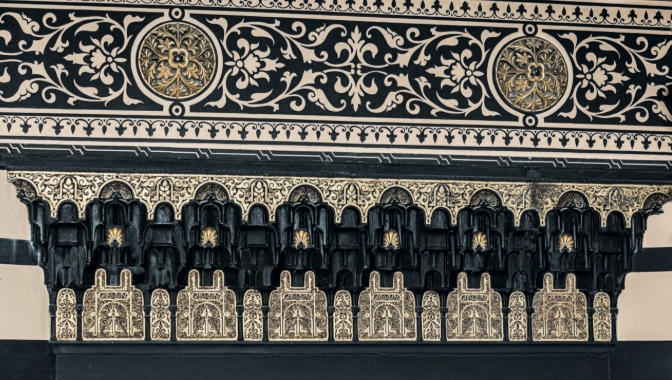

Fig. 7 One of a set of four panels on the upper walls of the Arab Hall Wood with pigments and gilding

Leighton House, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London

Fig. 8 Alcove in the Alhambra, Granada, showing a frieze with design of projecting stalactites similar to the Arab Hall panel in Fig. 7 (After Jules Goury and Owen Jones, Plans, Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra, London, vol. 1, 1842, pl. IX [detail])

La Zisa is a palace in Palermo, Italy, built between 1164 and 1175, during either the last two years of the reign of the Norman king William I (r. 1120/21–66) or that of his son, William II (r. 1166–89). Although there is no clear evidence that the architect visited this site, Leighton certainly did. He was in the city around 1875 and painted a watercolour of the interior of the Cappella Palatina (Leighton House, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London, acc. no. 20150001), a building lavishly decorated with mosaics, which may have served as additional inspiration for the concept of the ‘Arab Hall’. He also made drawings of the capitals at La Zisa (Robbins, 2011, p. 49). The building was quite dilapidated by this time: the Baedeker tourist guide of 1876 mentions that the only remains of the building were ‘a covered fountain … under honeycombed vaulting’ (Baedeker, 1876, p. 242). The guidebook fails to mention the remains of a mosaic frieze, which, however, appears in an engraving dated 1840 illustrating a history of the Normans in Sicily (see Gally Knight, 1840, pl. IV). Leighton may have had photographs taken of the interior since the artist Walter Crane mentions being sent a photograph of La Zisa’s mosaic frieze to demonstrate the type of design that he was being asked to produce for the ‘Arab Hall’ (Crane, 1907, p. 216). This would not have been unusual for Leighton: just two years earlier he had commissioned photographs of Damascus, mentioned in a letter to his father (Barrington, 1906, vol. 2, p. 208).

In his brief obituary of Leighton (Aitchison, 1896), Aitchison does not account for the inspiration behind the rest of the hall, which can in fact be traced to a range of architectural forms found in Spain, Egypt, Syria and Turkey, all countries visited by the artist. Aitchison had also travelled to some of these places: in his Royal Academy lectures published in 1903–4, the architect made direct references to buildings he had seen in Cairo, Granada and Constantinople (Aitchison, 1903, pp. 515 and 519; 1904, p. 57). Looking up towards the dome above the gold mosaic frieze designed by Walter Crane (see Fig. 6), the painted black-and-white stripes on the walls below the drum and dome recall the alternating black and white stone courses of the ablaq masonry typical of the Mamluk period (1250–1517) in Cairo and Damascus and mentioned in one of Aitchison’s earlier lectures (Aitchison, 1884, p. 299). The four curved triangular niches fitted into the corners within the striped banding indicate an Islamic method of supporting a dome known as a squinch; here, however, they are merely decorative.

Centred on the apex of each of these niches is a wood panel painted black and heavily decorated with gold (Fig. 7, see also Fig. 6). The colour scheme matches the woodwork of the rest of the house, but the design of projecting stalactites framed by panels of inscription is taken from the decoration of the Alhambra (Fig. 8). This complex of Nasrid dynasty (1238–1492 [in Granada]) palaces in Granada dating to the 14th century was much admired in the 19th century largely due to the publication of the two-volume work Plans, Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra, illustrated with details of the decoration of the buildings in colour (Goury and Jones, 1842 and 1845). The books were produced by the architect Owen Jones (1809–74), with the mapping and recording of the buildings accomplished jointly with architect Jules Goury (1803–34), who died in a cholera epidemic during the work.

Aitchison expressed his admiration for Owen Jones and his theories on the importance of colour in architecture in one of his first public lectures in 1857 (Aitchison, 1858, p. 52), and he was clearly familiar with the two volumes. The design on which the Arab Hall friezes are based is found in one of the alcoves in what Jones describes as the Patio de la Alberca or ‘Court of the Fish-pond’, now known as the Patio de los Arrayanes, or ‘Court of the Myrtles’ (see Goury and Jones, vol. 1, 1842, pl. IX). The Leighton House version is too high for the details to be clearly visible, but the close-up image in Figure 7 shows that both cursive and angular Kufic script are included on a ground of spiralling palmettes—just as in the original, although this was made of plaster, and painted in gold on red.

Fig. 9 Interior of the dome of the Arab Hall with coloured-glass windows

Leighton House, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London

A high dome rises over the octagonal drum (Fig. 9). According to Walter Crane, Leighton intended to commission him and the painter Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98) to add mosaics ‘when he was able to afford it’ (Crane, 1907, p. 216), but this never happened. The inspiration for the idea came from Byzantine architecture: the dome of the Cappella Palatina in Palermo, for instance, is lined with gold mosaics. The windows set into the dome copy the principle, if not the number, of those in the dome of Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul, built by the architect Sinan (c. 1488/90–1588) from 1550 to 1557, at the height of Ottoman supremacy (Fig. 10). Although today fitted with clear glass, at the time when Leighton and Aitchison visited this building (Leighton would have seen it in 1867; there is no information on the date of Aitchison’s visit), the dome windows were of coloured glass, an example of which was illustrated by the architect in one of his Royal Academy lectures (Aitchison, 1904, p. 57). According to William Wright, some of the windows for the ‘Arab Hall’ were acquired by him from a mosque in Damascus and others were manufactured in London (Wright, 1896, p. 184). Even the high, arched recesses on the north, south and west walls positioned just below the dome, although set with one rather than multiple windows, seem to be loosely based on the design of the imperial mosque in Istanbul.

Fig. 10 Interior of the dome of Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul, Turkey 1550–57 (Photograph by the author)

On the north and south sides of the hall, the base of each recess was upholstered with cushions on a wood banquette to serve as a window seat. The large, square windows above were fitted with differently patterned wood screens (mashrabiyya) (Fig. 11; see also Fig. 6). There is some confusion over the origin of the woodwork: Leighton’s friend and executor Samuel Pepys Cockerell (1844–?) mentions that they were ‘genuine musharabiyehs [mashrabiyya] bought in Cairo’ (Pepys Cockerell, 1900, p. 98), whereas Aitchison, as quoted above, refers to them as coming from Damascus (Aitchison, 1896, p. 265). Leighton, who went to both cities, would have seen examples in most of the houses he visited; composed of differently shaped wood elements slotted together without glue or nails to form an openwork grid, the panels provided dappled shade and ventilation as well as privacy (Gibson, forthcoming 2020). Urban reforms introduced in the Egyptian capital during the latter part of the reign of Muhammad ʿAli (1805–48) prohibited their use as outdated and a fire risk. This ban (which was not acted on universally) allowed foreign collectors to acquire examples in good condition, although it is not known if Leighton bought these screens, as well as those forming an enclosed balcony projecting from the first floor of the north side of the hall, on his 1868 Cairo trip or in London, where quantities of similar examples were collected by the South Kensington Museum (later the Victoria and Albert Museum) between 1869 and 1884, the same period in which the artist was commissioned to paint two frescoes for the South Court of the museum. Alternatively, as suggested by Aitchison, he or William Wright could have bought the screens in Damascus.

Fig. 11 North window of the Arab Hall with wood mashrabiyya screen Leighton House, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London

All four walls of the Arab Hall are covered with panels of tiles that excited the admiration and sometimes extravagant comments of visitors. The art historian Edgcumbe Staley (1845–?) described them as ‘… the most magnificent in Europe … not only priceless but entirely unique. They form the most sumptuous piece of monumental coloured decoration of modern times’ (Staley, 1906, pp. 111–12). Decorated with symmetrical floral patterns, inscriptions and occasional animal and human figures in tones of cobalt, turquoise, purple and bright green, almost all the tiles lining the hall were manufactured in Damascus in the second half of the 16th and early 17th centuries. A few are from Iznik in Turkey, and the four tiles set into the wood panel on the west wall, directly in front of the entrance, were made in Iran in two different periods: the two starshaped tiles in Kashan in the late 13th century and the two large tiles in the centre in early 17th century Isfahan. Many of the Damascus tiles were collected by Leighton himself on his trip to the city in 1873, and his guide William Wright continued to buy tiles for him there, with the sum of £42 being paid to him in January 1874 and £46 in June 1875 (Robbins, 2011, p. 23). Leighton’s friend Richard Burton (1821–90) was well placed to source examples since he was the British consul in Damascus from October 1869 to August 1871. In March 1871 he wrote to Leighton: ‘My wife and I will keep a sharp look out for you and buy up as many as we can find which seem to answer your description. If native inscriptions, white or blue for instance are to be had I shall secure them, but not if imperfect’ (Barrington, 1906, vol. 2, p. 219). It is unclear how successful the Burtons were in this promise, since they departed the city only a few months later. Caspar Purdon Clarke (1846–1911), a purchasing agent and later director of the South Kensington Museum, who spent five weeks in Damascus in 1877, succeeded in buying two matching panels: ‘I returned with a precious load, and in it some large family tiles, the two finest of which are built into the sides of the alcove of the Arab Hall’ (Purdon Clarke, 1883) (Fig. 12, left panel; for a view of both alcove panels, see Fig. 6).

Fig. 12 Tile panels on the northwest corner of the Arab Hall Both panels: Syria, Damascus, c. 1550–1650 Leighton House, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London is presently preparing a book on the Arab Hall at Leighton House.

With the exception of Purdon Clarke’s two panels, none of the tiles collected for display in the Arab Hall match—all were made in different sizes and decorated with a variety of floral patterns and inscriptions. Aitchison devised a scheme in which he successfully arranged the different patterns while not calling attention to the relative disparity of their designs and sizes. The panel of six tiles with the bismillah inscription that had been positioned under the stairs some years previously (see Fig. 4) was removed and incorporated into this new scheme (see the upper section of the right tile panel in Fig. 12).

Assembling and arranging the tiles to create a coherent and harmonious whole was a feat requiring considerable skill and the assistance of an experienced ceramicist who could make repairs to and replacements for the damaged tiles. William De Morgan, an acquaintance of both Leighton and Aitchison, was called upon for this task. A designer and craftsman of handmade ceramic tiles and vessels, he had opened his own studio at 36 Cheyne Row in 1872 and was therefore still relatively inexperienced when he received the commission from Leighton in 1877. His close handling and study of the tiles displayed in the Arab Hall over the two years of the commission were to give him an extraordinary insight into their design principles and techniques of manufacture and to guide his style throughout his career (Greenwood, 1989).

Leighton modestly credited his collaborators with the success of the Arab Hall: ‘He will tell you that all the merit of the building is due to the genius of Mr. Aitchison, his architect, that it is to Mr. De Morgan that he owes the perfection of the tiling of the Arab Hall—that many of the old tiles were missing and have been supplied by that gentleman, with perfect artistic sympathy; and that the designs of Mr. Walter Crane for the mosaics are the most beautiful thing of the kind he has ever seen’ (Monkhouse, 1882). The orchestration of the work may have belonged to others, but the vision behind the Arab Hall’s creation was clearly his own, a fact that was fully recognized by friends such as Emilie Barrington, who wrote in her biography of the artist: ‘It has been truly said that the Arab Hall is as notable a creation in Art as any of Leighton’s pictures or statues’ (Barrington, 1906, vol. 2, p. 221).

In Leighton’s own time some visitors to the ‘Arab Hall’ experienced it as an exotic, magical space evoking a setting from The Arabian Nights, a compilation of Middle Eastern folk tales, two English editions of which were published in the 1880s. The Reverend William Wright, Leighton’s guide and antique-buying companion in Damascus, called it an ‘oriental kiosk’ (Wright, 1896, p. 184), in recognition of its inspiration in the arts and crafts of the Middle East. Frederic Leighton himself, in a memorable throwaway comment, described it as ‘a little addition for the sake of something beautiful to look at once in a while’ (Hawthorne, 1928, p. 138). In line with his aesthetic beliefs, the beauty and harmony of his ‘Arab Hall’ were its most important qualities, and to this day they inspire universal admiration.

Melanie Gibson is a trustee of Leighton House, executive trustee of the Gingko Library and senior editor of the Gingko Art Series. Her publications focus on the ceramics and glass of the Islamic world as well as the reception and use of Islamic patterns in 19th century British design. She is presently preparing a book on the Arab Hall at Leighton House.

The major restoration and refurbishment of Leighton House Museum is due to be completed in summer 2021. From January 2020, the house is open only at the weekend.

Selected bibliography

George Aitchison, ‘Coloured Glass’, Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects XI (1904): 53–65.

—, ‘Coloured Terracotta’, Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects X (1903): 513–22.

—, ‘Lord Leighton P.R.A. Some Reminiscences’, Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects III (1896): 264–65.

—, ‘Colour’, The Art Journal (1884): 297–300.

—, ‘On Colour as Applied to Architecture, 14 December 1857’, Papers Read at the Royal Institute of British Architects (1858): 47–60.

K. Baedeker, Italy, Handbook for Travellers, Third Part, Southern Italy and Sicily, London, 1876.

Emilie Barrington, The Life, Letters, and Works of Frederic, Baron Leighton of Stretton, 2 vols, London, 1906.

Walter Crane, An Artist’s Reminiscences, London, 1907.

Caroline Dakers and Daniel Robbins, George Aitchison: Leighton’s Architect Revealed, London, 2011.

Henry Gally Knight, Saracenic & Norman Remains, to Illustrate The Normans in Sicily, London, 1840.

Melanie Gibson, ‘Mashrabiyya’, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, third edition, forthcoming 2020.

Jules Goury and Owen Jones, Plans, Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra, 2 vols, London, 1842 and 1845.

Martin Greenwood, The Designs of William De Morgan, London, 1989.

Julian Hawthorne, Shapes that Pass: Memories of Old Days, London, 1928.

Cosmo Monkhouse, ‘Sir Frederick Leighton’s Studio’, Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 16 October 1882, p. 6.

S. Pepys Cockerell, ‘Lord Leighton’s House in 1900’, in Ernest Rhys, Frederic Lord Leighton: An Illustrated Record of His Life and Work, London, 1900, pp. 92–102.

Caspar Purdon Clarke, memo dated 6 June 1883, ‘Sir C.P. Clarke’s visit to Asia Minor’, Victoria and Albert Museum Archive, 84/3451.

Daniel Robbins, Leighton House Museum: Holland Park Road, Kensington, London, 2011. Edgcumbe Staley, Lord Leighton of Stretton, New York, 1906.

William Wright, ‘Lord Leighton at Damascus and After’, The Bookman IX (March 1896): 183–85.