A Visit to the Buddhist Sites of Gandharan Pakistan

Christine M.E. Guth

1.

Participants of the International School on Gandharan Buddhism at Saidu Sharif Stupa Swat District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, January, 2025

1st–5th century CECE

Photo courtesy of Amir Khan

Between January 9 and 18, 2025, forty scholars participating in the first International Winter School on Gandharan Buddhism representing fourteen countries and twenty institutions had the rare opportunity to visit some of the historic sites of ‘Greater Gandhara’, a region that includes Taxila, the Peshawar basin, and Swat in northwest Pakistan (fig. 1). Although not a specialist in Gandharan art, I was fortunate to be able to join the group for an eleven-day study trip that brought me full circle, having begun my graduate school studies in the 1970s under Benjamin Rowland and John Rosen-field, both American scholars of Gandharan art. At that time, the study of Buddhist art was based largely on fragments of narratives of the Buddha’s life or on iconic images of buddhas and bodhisattvas of lost or unknown provenance housed in museums. Most were simply identified as ‘from Gandhara’. There was no unanimity about how that region was defined or the chronology of its material remains. Since then many more sites in Pakistan have been excavated, and stratographic and epigraphic investigations have laid the foundations for far more systematic study, but nothing can equal actual travel to Pakistan to appreciate the physical and human ecosystem that shaped the development of Gandharan Buddhist culture.

2.

Takht-i-Bahi Complex

Mardan District of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, January, 2025

2nd–7th century CE

Photo courtesy of Dr Anwar Numan

Bounded to the west by the Indus River, to the east by the Swat River, and to the north by the Hindu Kush, Gandhara’s geographic location at the intersection of multiple trade routes made it the setting for dynamic intercultural encounters among Europe, West Asia, India, Central Asia, and China. Buddhism flourished there under the successive ruling dynasties of the Mauryan kings (322–185 BCE), the Indo-Greeks (200 BCE–50 CE), and the Kushans (30–375 CE), but especially between the 3rd to mid-5th centuries. The intrepid 7th-century Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang (602–664 CE) travelled south into Gandhara, on foot, after crossing the snow-capped Hindu Kush mountain range. We travelled more comfortably in the opposite direction, north from the modern capital city of Islamabad, in a convoy of minibuses escorted by security guards, speeding along a modern highway and overtaking large trucks elaborately painted with colourful floral motifs. Like Xuanzang, we stopped in the city of Peshawar, once known as Purushapura, the capital of the Kushan empire, whose rulers, especially Kanishka (r. 127–150 CE), were influential Buddhist patrons. From there we travelled into the fertile Swat Valley, the place Xuanzang called Wuzhangna—rendered in Sanskrit as Uddiyana meaning ‘garden’ or ‘orchard’. The peach, apple, apricot, and persimmon trees for which it is famous were still devoid of foliage, but the fields were already green with winter wheat, rapeseed, and leafy green vegetables. Just as the agricultural riches of Swat fuelled the growth of ancient Buddhist monastic complexes, they underpin the local economy today.

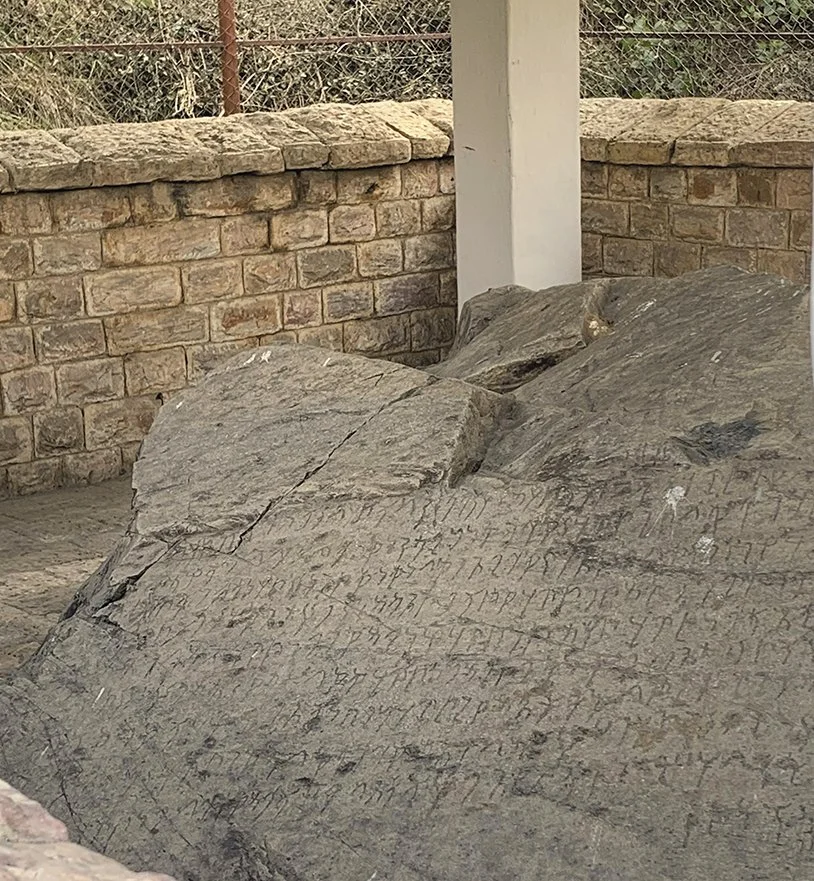

3.

Ashokan edict at Shabaz Garhi

Mardan District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan,

January, 2025

Mid-3rd century CECE

Reliquary mounds, stupas, monasteries, narrative reliefs, freestanding images, and rock inscriptions provide critical ma-terial evidence of Buddhism in Greater Gandhara from the 1st century BCE until the 6th century, with better-protected complexes located at higher elevations such as Takht-i-Bahi remaining active until the 7th century. Their strategic distribution reflects both pious patronage by successive rulers and the location of trade routes linking the region with Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. While some monasteries, such as those in the vicinity of Sirkap and Barikot, were built near bustling cities, others, such as the stupa complex at Amluk Dara, developed in sites of natural beauty along multi-faith pilgrimage routes. Whether urban or rural, the construction of a stupa to hold relics of the Buddha was a meritorious act, requiring a substantial investment in human as well as material resources: architects to plan and oversee the project, sculptors, and men to quarry the stone, as well as a large contingent of manual workers. Rulers who carried out such pious activities were rewarded with economic power and social prestige.

4.

Detail of stupa at Jaulian Monastery, showing diaper masonry construction

Taxila, Punjab, Pakistan, January, 2025

2nd century CECE

Takht-i-Bahi, in the Mardan district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (PK) Province, exemplifies Xuanzang’s observation that ‘the stupas and sangharamas [in this region] are of an imposing height, and are built on high level spots, from which they may be seen from every side, shining in their grandeur’ (Xuanzhang, 1884, p. 55) To reach the fortress like complex, we climbed many flights of stairs wide enough to accommodate large numbers of tourists. It was the only space we shared with local families, vacationing children in tow, all eager to picnic atop the five-hundred-metre-high mountain and take in a dramatic view of the city of Mardan and the surrounding area (fig. 2). Our guides, however, complained that the six to eight thousand locals who visit the site on weekends have little appreciation for the monument’s historical significance because school textbooks do not include any pre-Islamic Pakistani history. Carved out of the hillside in stages between the 2nd and 7th centuries, Takht-i-Bahi comprises a series of terraces joined by narrow stairways. One terrace features a central stupa with other smaller stupas so tightly packed around it that it is difficult to imagine how a devotee might circumambulate it. On a lower level, a row of small, windowless meditation cells access to which required almost crawling on hands and knees was carved into the mountainside. These are thought to date from the latest period, when Tantric Buddhism was practiced here.

5.

Detail of votive stupa at Jaulian

Monastery, showing stucco frieze with buddhas, bodhisattvas, and divinities

Taxila, Punjab, Pakistan, January, 2025

2nd century CE

Shahbaz Garhi, also in the Mardan district, is the site of two of fourteen edicts pertaining to codes of conduct that King Ashoka (272–232 BCE) ordered carved in stone across the Mauryan empire. These covered much of the Indian subcontinent, including parts of modern Pakistan and Afghanistan. They do not mention the Buddha or sangha (Buddhist monastic community), but because they are framed by the word dharma (Buddhist teachings), the edicts have been taken as evidence that Ashoka was an adherent of Buddhism. They were carved into large boulders that earthquakes have dislodged from their original locations atop a mountain, along a route that was once frequented by traders. Edict Number 12, repro-duced in figure 3, decrees tolerance of different religious sects. The inscription is written in the Gandhari language using Kharosthi script. Although the use of both the language and script seems to have died out around the 5th century, they are critical to recovering Buddhist history, since the earliest surviving scriptures, inscribed on birchbark, were written in this form. Taxila, according to popular etymology, gets its name, meaning ‘city of stones’, from taka (cut) and shaila (stone). In and around the Buddhist complexes there we saw evidence of the craftsmanship for which this region has been famous since ancient times. Small workshops sold polished black schist gravestones and tomb surrounds with incised décor, as well as articles for domestic use, such as spice mills, mortars, and ashtrays made of local stones. A few more daring craftsmen sold miniature Buddhist stupas and figures, despite the 1975 Antiquities Act that forbids making replicas of any kind.

6.

Remains of seated Buddha and feet of Buddha or bodhisattva, Jaulian Monastery

Taxila, Punjab, Pakistan, January, 2025

2nd century CE

The stupas and monasteries in the Taxila region are constructed using a sophisticated diaper masonry technique, in which a decorative pattern is created by setting large, flat, circular stones within a framework of smaller horizontally arranged ones. This characteristic building technique was adopted at the ruined Buddhist monastery of Jaulian and also in its restoration, often making it difficult to determine where the original begins and ends (fig. 4). With a central masonry reliquary mound surrounded by many smaller ones and an adjacent monastery, the layout of Jaulian is typical of many of the complexes in Greater Gandhara. The living quarters for monks face the main stupa, of which only the base remains. At Jaulian the cells, each with a small, window-like slit for air and light, are arranged on two stories. These are organized around a central courtyard with a shallow quadrangular pond that supplied water for various needs. The visual coherence of most Gandharan complexes is lost because the narrative programs displaying scenes from the life of the Buddha that decorated the walls of the relic mounds have been plundered or removed, for safety, to local museums. At Jaulian, however, many reliefs are still affixed to the cluster of small votive stupas built around the main reliquary mound. They are crafted over the masonry core in moulds using lime plaster finished with finer stucco, a medium that allowed for mass production. The reliefs form long friezes with repeating images of seated buddhas flanked by divine beings or bodhisattvas, separated by columns (fig. 5). Individual patrons also donated over-life-size images of buddhas and bodhisattvas, whose traces can be seen in small shrines around the periphery of the compound (fig. 6).

7.

Double-Headed Eagle Stupa, Sirkap

Taxila, Punjab, Pakistan, January, 2025

1st century BCE–1st century CE

The nearby city of Sirkap has a remarkable, multi-layered history that materializes the successive religious waves that swept the region. It was first built in the 2nd century BCE by the Greco-Bactrian King Demetrius (r. 294–288 BCE) following a grid plan, but over the centuries the Greek-style city was overlaid with Buddhist, Jain, Hindu, and Zoroastrian structures. The discovery in 1935 of a Christian cross near the ruins has even given rise to the legend that Saint Thomas visited Taxila. On the basis of numismatic evidence, Sirkap’s stupas are believed to be among the oldest in Gandhara, datable between the 1st century BCE and the first half of the 1st century ce .

8.

View of Swat River Valley from top of Barikot

Swat District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, January, 2025

Photo courtesy of Dr Anwar Numan

They show the characteristic form of Gandharan stupas: a square base with a central stairway, leading to a platform topped by a domed structure holding relics, around which devotees cir-cumambulated. In this respect they differ from their counterparts at Sanchi and Bharhut, where the hemispherical reliquary mound rests directly on the ground. The so-called Double-Headed Eagle Stupa exhibits this square foundation (fig. 7). It gets its name from the unusual décor flanking the stairway, contained within three niches separated by pilasters with Corinthian capitals. In the niche to the viewer’s left is a representation of a Greek-style temple entryway with a triangular gable; in the centre, an ogee-shaped entrance to a chaitya (Indian temple); and on the right, a two-tiered ornamental tora-na (gateway). The double-headed eagle that crowns the central structure, a motif thought to be of Scythian origin, has long attracted the attention of European visitors because it is echoed in the coat of arms of the Hapsburg empire.

9.

Remains of apsidal structure at Barikot

Swat District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, January, 2025

Maurya dynasty (322–185 BCE)

Enclosed by mountains and irrigated by the Swat River, which forms a north-south spine through it length, the epony-mous valley was a flourishing centre of Buddhism. Dominated by a steep, rocky hill overlooking the winding river, the city of Barikot (known as Bazira in ancient times) has an exceptionally long history dating back to the Bronze Age (c. 1700 BCE), owing to its strategically important location for control of the valley’s riches (fig. 8). The city became a thriving multi-cultural metropolis under the Kushans, at which time fortifications and a water tank with a sophisticated hydraulic system were built atop the hill, but their waning power and a series of earthquakes led to Barikot’s decline. Excavations carried out by the Italian Archaeological Mission since the 1980s have been critical in bringing to light the many strata of Barikot’s his-tory, as well as artifacts testifying to the coexistence of local and Hellenistic beliefs and practices following Alexander the Great’s (356–323 BCE) conquest of the region in 327 BCE. Among the most recent discoveries, in 2023, are the remains of a ten-foot high apsidal structure rebuilt over the foundations of an earlier non-Buddhist shrine dating from Alexandrian times (fig. 9). Thought to date from Mauryan times, it confirms the practice of Buddhism in the region as early as the 3rd century BCE.

About thirty kilometres north of Barikot, the Jehanabad Buddha, six metres in height, is carved into a huge rock face that occupies a commanding position at the head of a valley near the village that gives it its name (fig. 10). It depicts the Buddha seated in meditation wearing a robe covering both shoulders, its folds forming concentric curves falling from the right shoulder. Believed to date from the 7th century, it was once part of a religious complex of which a few remains are still visible on nearby outcroppings. It is reached by a trek through orchards and villages where children play and goats graze, and finally a steep climb up narrow rock-cut stairs. Its elevated position protected it until 2007, when the Taliban, then in control of the area, tried to deface it with rockets and explosives. Fortunately, only the face was damaged. Between 2012 and 2016, the Italian Archaeological Mission, in collaboration with provincial and federal archaeological authorities, repaired it. In keeping with current protocols, the restoration recaptures its original appearance while leaving no doubt that it is a modern reconstruction.

10.

Jehanabad Buddha

Swat District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, January, 2025

7th century CE

Not far from the city of Mingora, where the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Malala Yousafzai was born in 1997, lies the site known as Butkara I. Its stupa, first built during the Mauryan period and rebuilt in many phases, remained an important pil-grimage site until the 11th century. Unique among Gandharan sites, the path around the stupa was covered with luxurious lapis lazuli tiles, a few of which are still in situ. Today, Butkara is best known for what many scholars believe to be the oldest anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha in the region (fig. 11). Dating to the first or second century CE, this seated figure was made at the same time as the first images of the Buddha in Mathura, far to the south, in modern India. Current excavations at Butkara I focus on developing a better understanding of the relationship between this complex and the adjacent city. As we toured the main route leading to the sanctuary, the Italian archeologist Dr Elisa Iori, who has played a key role in its excavation, told us that large storage vessels used for food and drink, as well as grinding stones and other tools for stonework, had been excavated there. These material remains underscore her observation that Buddhist complexes were ‘efficient machines’ whose economy depended on a well-coordinated human infrastructure.

Amluk Dara, one of the largest stupas in Swat, was built in the late first century CE, when the area was under Kushan rule (fig. 12). We do not know the original names of most stupas, and today they are identified by their location: Amluk Dara means ‘Persimmon Hill’ in the local Pashto language. It occupies a commanding position at the head of a scenic orchard-filled valley on the route leading to Mount Ilam, a 2,800-metre-high peak sacred to Hindus, believed to be the site of the god Rama’s throne. Its imposing square base and long stairway leading to the podium and the reliquary mound above are visible from a considerable distance. In its original state, the dome would have been more imposing still, since it was topped with chattra (multi-tiered umbrella-shaped spires) made of stone. Seeing these colossal stones, which lie where they fell from the stupa, offers a glimpse of the extraordinary technological skill and human labour, not to mention economic resources, that went into the construction of this monument.

11.

Remains of Seated Buddha statue at Butkara

Swat District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, January 2025

1st century to 2nd century CECE

Conservation of Amluk Dara and other Buddhist complexes is an ongoing and serious concern for local authorities. The annual rains that nourish the crops also feed the growth of plants that damage the stupa’s masonry. In the absence of cranes and other industrial equipment, workers, precariously perched on long ladders, must weed the domes by hand every year. Protection of these sites from looters is also a consideration. Amluk Dara lies in the vicinity of hamlets whose residents can be hired as twenty-four-hour guards, but it is difficult to find men willing to camp out in tents at below-freezing weather in more remote, windblown hilltop sites like Tokar-Dara, where the remains of a monastery, stupa, assembly hall, and nearby aqueduct can be seen. Local and national Pakistani government authorities hope that greater awareness of and travel to the historic monuments of the Gandharan region will further advance their conservation efforts.

Christine Guth is a historian of Japanese art with a longstanding interest in the Buddhist art of Gandhara.

12.

Stupa at Amluk Dara

Swat District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, January, 2025

Late 1st century CECE

This study trip was made possible with the sponsorship of the Waksaw Uddiyana Archeological Alliance, USA; Taxila Institute of Asian Civilizations (TIAC), Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad; the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province; the Ministry of Science and Technology of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; the Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation; and the Woodenfish Foundation. Our hosts and scholarly guides included Dr Ghani-ur-Rahman of Quaid-i-Azam University, Dr Subhani Gul, Dr Abdul Samad and Dr Fawad Khan of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums (DOAM) of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Mr Nawaz ud Din, curator of the Swat Museum, and others too numerous to name individually. Our travels in KP were ably coordinated by Dr Numan Anwar, representing the DOAM of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province. Thanks are also due to Dr Stefan Baums of Ludwig-Maximiliar University, Munich; Dr Elisa Iori of Ca’ Foscari University, Venice, and the deputy director of the Italian Archaeological Mission in Pakistan; and Dr Dessie Vendova of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, who shared their knowledge of Gandharan epigraphy, archaeology, and art to illuminate the historical, political, linguistic, and religious contexts in which the religious monuments we visited were built and used. Personal thanks also to Yunyao Zhai and Dessie Vendova for their help in the preparation of this article.

All photos by the author unless otherwise indicated.

Selected Bibliography

Stefan Baums and Andrew Glass, Gandhari.org (blog), accessed April 22, 2025, https://gandhari.org.

Kurt A. Behrendt, The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhara, Leiden, 2004.

The Geography of Gandhāran Art: Proceedings of the Second International Workshop of the Gandhāran Connections Project, University of Oxford, 22nd–23rd March 2018, ed. Wannapron Rienjang and Peter Stewart, Oxford, 2019.

Luca M. Olivieri, Stoneyards and Artists in Gandhara: The Buddhist Stupa of Saidu Sharif I, Venice, 2022, http://doi.org/10.30687/978-88-6969-578-0.

Luca M. Olivieri and Elisa Iori, ‘Monumental Entrance to Gandharan Buddhist Architecture: Stairs and Gates from Swat’, Annali di Ca’Foscari. Serie Orientale 57 (June 2021): 197–239, http://doi.org/10.30687/AnnOr/2385-3042/2021/01/009.

John M. Rosenfield, The Dynastic Art of the Kushans, Berkeley, California, 1967.

Xuangzang, Records of the Western Kingdoms, trans. Samuel Beal (1884), at Silk Road Seattle, ed. Daniel C. Waugh, Walter Chapin Simpson Center for the Humanities, University of Washington, https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/xuanzang.html.