Image 1 of 1

Image 1 of 1

JAN/FEB 2021

VOLUME 52 - NUMBER 1

Throughout time, rulers have commissioned buildings and art to establish and communicate their power. In China, a prime example is the use of bronzes in rituals, starting around 2000 BCE. Three-dimensional vessels such as a wine cups were made for the wealthy elite and associated with power. It was not until the Warring States period (475–221 BCE) that flat bronze plates appeared. They were often inscribed with imperial edicts or pictorial scenes and were a way to meet the demands of announcing and recording important laws and events as they were easier to produce than three-dimensional objects.

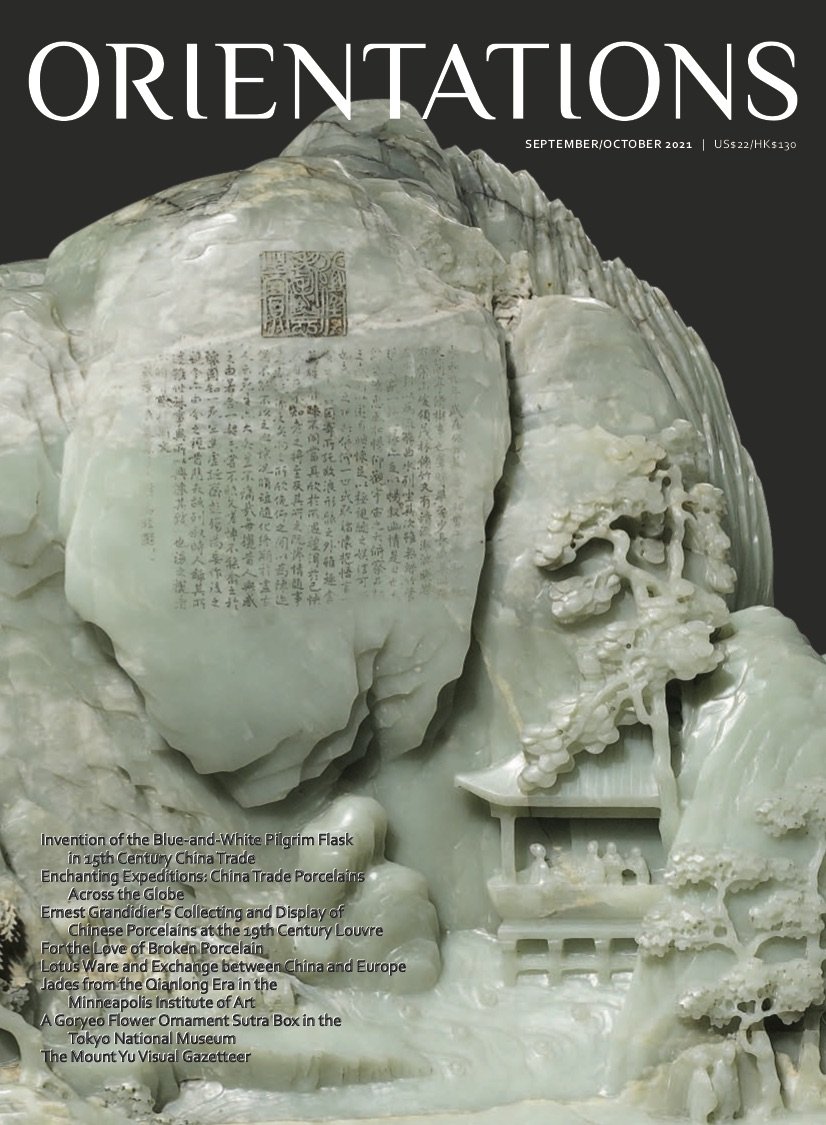

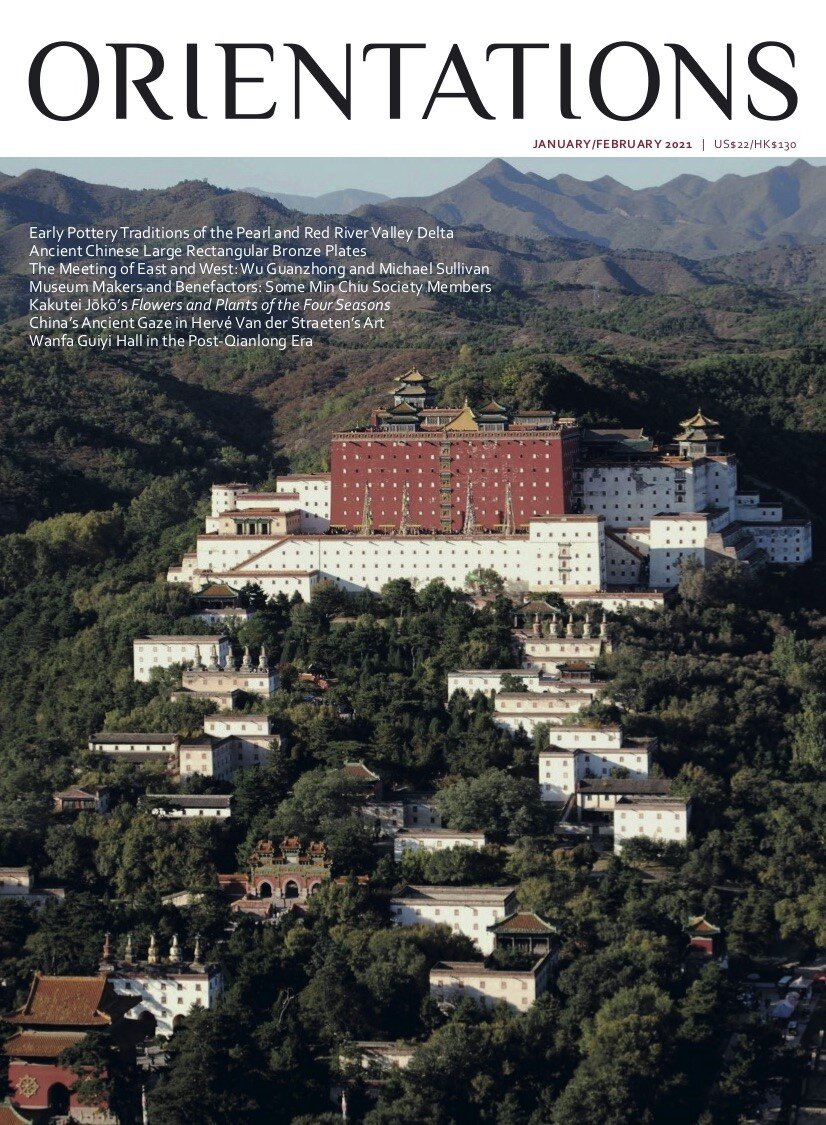

The reign of the Qianlong emperor (1735–99) was one of great prosperity and cultural development. To celebrate his achievements near the end of his life, he built a complex of Buddhist temples in Chengde called ‘the Little Potala’, modelled after the Potala Palace in Lhasa. Despite being built at the pinnacle of Qing dynastic power, the Little Potala, and specifically the main Wanfa Guiyi Hall, suffered continuous decline almost immediately after its construction.

After the end of WWII, many of China’s industrialists and educated elites relocated to Hong Kong and Taiwan, bringing with them a literati tradition of studying the classics and collecting antiquities. Min Chiu Society was established in Hong Kong in 1960 as a private group that regularly met to view each other’s collections and share ideas. To mark the group’s 60th anniversary, the exhibition ‘Honouring Tradition and Heritage’ opened this December at the Hong Kong Museum of Art with over three hundred works from the collections of the society’s members. We share notable figures in the history of the society and their generous bequests to museums.

French-educated artist Wu Guanzhong (1919– 2010) was one who remained in China after WWII. When China reopened its doors to the West after the Cultural Revolution, Wu was able to share his art theories—controversial at the time—through an exchange of letters with Michael Sullivan (1916– 2013), a scholar of modern Chinese art. The two developed a longstanding friendship, and Sullivan introduced Wu’s works to Western audiences.

The Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture and the Kobe City Museum held a joint exhibition on the works of Kakutei Jōkō (1722–86) in 2016. A close look at a pair of six-panel folding screens measuring 170 centimetres in height and 370 centimetres in width depicting flowers and plants of the four seasons in the Saint Louis Museum reveals insights into the artist’s life as a monk of Obaku, one of the three largest Zen schools.

Hong Kong held two physical art fairs at the end of November: Fine Art Asia and Hong Kong Spotlight by Art Basel. The time-slot entries, greater sanitation measures and social distancing enticed a bigger-than-expected crowd. Despite digital innovations to bring art to people in their homes, there is nothing that can replace seeing the real objects in person.

FEATURES

Baihua Li. A Preliminary Study on Ancient Chinese Large Rectangular Bronze Plates

Jin Xu. Evanescent Temple, Eternal Dharma. The Wanfa Guiyi Hall in the Post-Qianlong Era of the Qing Dynasty

Richard A. Pegg. Early Pottery Traditions of the Pearl River Valley and Red River Valley Delta

Peter Y. K. Lam. Museum Makers and Benefactors. Some Min Chiu Society Members

Nadia Sheung-ying Lau. The Meeting of East and West: Wu Guanzhong and Michael Sullivan

On-Tsun Fung. To the Roots of Kakutei Jōkō's Flowers and Plants of the Four Seasons

Sarah Handler. China's Ancient Gaze in Hervé Van der Straeten's Art

PREVIEWS & REVIEWS

Nancy Steinhardt. Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800 by Jonathan Bloom

INTERVIEWS

An Interview with Shing Yiu Yip, Chairman of Min Chiu Society

CURATOR’S CHOICE

Birgitta Augustin. 'Like stars seen on the bottom of deep wells': Recalling a Shakyamuni in Detroit

VOLUME 52 - NUMBER 1

Throughout time, rulers have commissioned buildings and art to establish and communicate their power. In China, a prime example is the use of bronzes in rituals, starting around 2000 BCE. Three-dimensional vessels such as a wine cups were made for the wealthy elite and associated with power. It was not until the Warring States period (475–221 BCE) that flat bronze plates appeared. They were often inscribed with imperial edicts or pictorial scenes and were a way to meet the demands of announcing and recording important laws and events as they were easier to produce than three-dimensional objects.

The reign of the Qianlong emperor (1735–99) was one of great prosperity and cultural development. To celebrate his achievements near the end of his life, he built a complex of Buddhist temples in Chengde called ‘the Little Potala’, modelled after the Potala Palace in Lhasa. Despite being built at the pinnacle of Qing dynastic power, the Little Potala, and specifically the main Wanfa Guiyi Hall, suffered continuous decline almost immediately after its construction.

After the end of WWII, many of China’s industrialists and educated elites relocated to Hong Kong and Taiwan, bringing with them a literati tradition of studying the classics and collecting antiquities. Min Chiu Society was established in Hong Kong in 1960 as a private group that regularly met to view each other’s collections and share ideas. To mark the group’s 60th anniversary, the exhibition ‘Honouring Tradition and Heritage’ opened this December at the Hong Kong Museum of Art with over three hundred works from the collections of the society’s members. We share notable figures in the history of the society and their generous bequests to museums.

French-educated artist Wu Guanzhong (1919– 2010) was one who remained in China after WWII. When China reopened its doors to the West after the Cultural Revolution, Wu was able to share his art theories—controversial at the time—through an exchange of letters with Michael Sullivan (1916– 2013), a scholar of modern Chinese art. The two developed a longstanding friendship, and Sullivan introduced Wu’s works to Western audiences.

The Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture and the Kobe City Museum held a joint exhibition on the works of Kakutei Jōkō (1722–86) in 2016. A close look at a pair of six-panel folding screens measuring 170 centimetres in height and 370 centimetres in width depicting flowers and plants of the four seasons in the Saint Louis Museum reveals insights into the artist’s life as a monk of Obaku, one of the three largest Zen schools.

Hong Kong held two physical art fairs at the end of November: Fine Art Asia and Hong Kong Spotlight by Art Basel. The time-slot entries, greater sanitation measures and social distancing enticed a bigger-than-expected crowd. Despite digital innovations to bring art to people in their homes, there is nothing that can replace seeing the real objects in person.

FEATURES

Baihua Li. A Preliminary Study on Ancient Chinese Large Rectangular Bronze Plates

Jin Xu. Evanescent Temple, Eternal Dharma. The Wanfa Guiyi Hall in the Post-Qianlong Era of the Qing Dynasty

Richard A. Pegg. Early Pottery Traditions of the Pearl River Valley and Red River Valley Delta

Peter Y. K. Lam. Museum Makers and Benefactors. Some Min Chiu Society Members

Nadia Sheung-ying Lau. The Meeting of East and West: Wu Guanzhong and Michael Sullivan

On-Tsun Fung. To the Roots of Kakutei Jōkō's Flowers and Plants of the Four Seasons

Sarah Handler. China's Ancient Gaze in Hervé Van der Straeten's Art

PREVIEWS & REVIEWS

Nancy Steinhardt. Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800 by Jonathan Bloom

INTERVIEWS

An Interview with Shing Yiu Yip, Chairman of Min Chiu Society

CURATOR’S CHOICE

Birgitta Augustin. 'Like stars seen on the bottom of deep wells': Recalling a Shakyamuni in Detroit